The Double Life and Hard Times of Bart Adam Young

By Robin Postell

(First published in Razor Magazine)

Darkness shuts down another day in the Cook County Jail in Adel, Georgia, where burgeoning outlaw country star Bart Adam Young, 34, stretches out on his bottom iron bunk. Since being nabbed during a raid in an old trailer out on Lover’s Lane nearly two months ago, he’s been here, unable to bond out because of the $175,000 price tag.

“Sing a song, Bart,” calls out one of his cellmates. This has become a nightly ritual for his fellow inmates. They know the tune will accompany a tale, and they wait.

“Tell us about when your brother chased down Kid Rock’s bus,” calls out another, and Bart clears his throat.

“Alright,” he starts, but waits, in thought, wondering what would’ve happened back in 2000 if it hadn’t happened at all. He and his wife of seven years, Kristie, and his babies, had been making it day to day –struggling, yes, but a family. Brett, his baby brother, had, as always, provided the extra nudge Bart needed to keep chasing the dream that might take them out of this little Georgia town, make ‘em somebody.

“That bus got me in this cell with you motherfuckers,” he begins, and everybody laughs. “But naw, I reckon it ain’t that simple.”

He idles, clearing his throat again, thinking, his audience rapt.

Bart begins the whole mad tale, lost in memory.

+++

Brett, three years younger, had always been Bart’s cattle prod – blasting him forward to make it happen by using the blessing the Lord had given him. They’d keep bands going, and sometimes success would brush against them.

“But I’d do something to piss somebody off most of the time, and Brett’d say, ‘Bart, you can’t be telling them record folks to fuckoff like that, you gotta learn how to work with ‘em,’ but I’d say, ‘Brett, I ain’t changin’ for no goddamn body. It’s mine,’” Bart says, remembering all those close calls, unsigned deals left on tables.

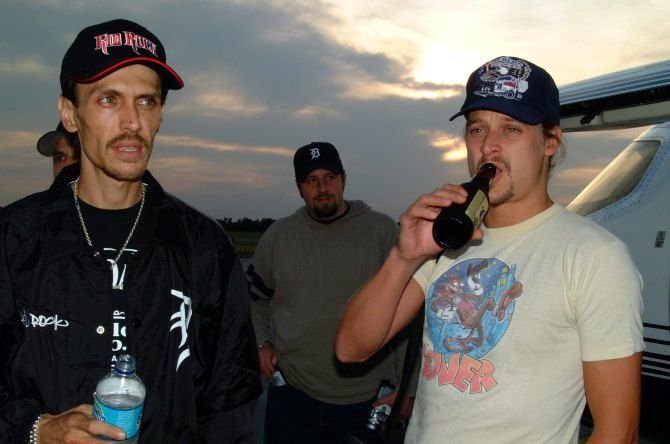

Nearly ready to give up, Brett kept on Bart, “about this Rock dude, some Detroit cowboy rapper wantin’ to be country,” Bart says, “and I said, ‘Who’s Kid Rock?’ because I ain’t never heard of him, and he tried to get me to listen to his music, but I said, ‘Naw, brother, you know that ain’t me.’”

Brett had seen Rock on CMT with Hank Williams, Jr., and he said, “Bart, he’s gonna get you, I swear he’s all into country now, he’ll finally be the one who’s gonna get it.”

Bart continues, “He got it in his head he was gonna go ambush one of this cat’s concerts in Birmingham. I said, ‘Go, but I ain’t going.’ I hate going to shows and shit like that. I told him, ‘Give him my demo, you know damn well he’s gonna like it.’”

Brett and friend Bruce King drove to Alabama and hovered around like, fat, ugly groupie chicks begging to get past security, with three demos in hand – but they never saw Rock. Tired and mad, Brett couldn’t let it go; he got his second wind and said, “Dammit, we’re gonna follow those tour buses.”

From Alabama to Kentucky, they trailed behind for nearly nine hours. No longer able to ignore their determined stalkers, Rock’s security, reputed to be comprised of former Special Forces agents and Indian Outlaw motorcycle gang members (of which Rock had been named an honorary member) exited the buses. Packing heat, they let Brett and Bruce know they weren’t fucking around; they had no patience for crazy fans wanting an autograph and a kiss.

Brett humbly made his pitch. “Look, we’re from Adel, Georgia, and I just gotta get this demo of my brother, Bart Adam Young, to Rock. He’s gonna love it. It is destiny, it’s fate, so don’t just toss it into Roadside Records (referring to the trashcan).” Noting Brett’s obvious lack of threat – tall lanky, yellow ponytail hanging down his spine – Rock’s protectors eased up, realizing they were just a couple of wannabes.

Uncle Kracker, one of Rock’s pet projects on the tour with him, had overheard the entire episode and made sure the tape got to Rock.

As Rock puts it later, “Kracker game me the tape and told me about them following the bus for eight hours. I listened to it and it sounded so original. Everything’s so cookie-cutter in Nashville now, and this was so raw. I called Bart up and said, ‘Hey man, you writing all this stuff?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, other than a couple I had a co-writer on,’ and I invited him to come to a show I was doing in Charlotte with David Allan Coe.”

Bart, oblivious to Rock’s status, agreed. “But when we got there, backstage, we were mostly ignored, and I was getting pissed off. I didn’t give a fuck whether I met the sumbitch or not at that point,” Barts says. “I ain’t no goddam fan.”

This, I knew, was not a boastful bit of bombast. Bart was not up to speed on anything in the pop culture world, seemingly forever trapped in a bubble of old-style country outlaw music and its artists.

Coe, however, figured big in Bart’s upbringing, and he often covered some of his songs.

“Brett said, ‘Aw, he’s just feelin’ you out, man, let him see you,’” explains Bart. “Brett pays attention to shit like that, and I reckon he was right because Little Bear, Rock’s head security dude, came over and said, ‘Hey, Bart, it’s your time,’ and let me out back where the buses were. Rock and Coe were on Coe’s bus.”

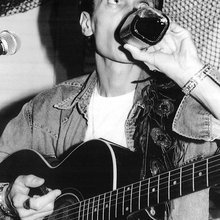

They handed David Allan Coe’s guitar to Bart and Rock said, “Alright, show me what you got, brother.”

Bart sat down, started up, and Rock’s face changed, electrified.

“Yeah, he was playing this music of his and David looked at me and said, ‘This kids’ the real deal, he’s got it,’” Rock recalls. “And I said, ‘I think you’re right.’”

Rock promised a deal, saying, “I’ll either get you one or give you one, but just give me some time.”

After chasing a dream for so long, then grabbing it, the boys reeled. They went back home and told everybody about meeting Rock. But nobody believed them. Bart kept playing gigs, waiting. Pressure mounting, drinking wasn’t enough. Brett started doing ecstasy and cocaine, and Bart followed, but they wore out the high. Then somebody introduced them to methamphetamine.

Bart’s habit got big, fast. Tearing off a sleeve of tinfoil, he’d crumble up the gritty powder onto it, melt it down with a low-flame lighter and suck up the resulting smoke from a straw.

“And that was it,” Bart says. “I’d found my high. I didn’t want to do anything else. Killed my taste for alcohol, coke, everything. I could stay up for days. I’d get three-, four-days-old, and there wasn’t nothing like it.”

Rock remained loyal and asked the boys up to Detroit in mid-2002 to his private home studio. During this four-day period, a master of Bart’s music was made, with the intention of shopping it around to different labels, hoping to sign him to an 18-month development deal.

“We want to keep it contained, keep it real,” says Rock. “Make sure it doesn’t get watered down.”

Rock invited to open back-t0-back for him in his hometown of Detroit in 2003. Lynyrd Skynyrd would also be on the bill. Bart, who’d never played a crowd like the oe that would be gathered in the Joe Louis Arena for two such powerhouses, told Rock, “Man, I ain’t never played a crowd that big and al I got it this little shitty guitar.”

But Rock said, “Man, if you’re writing songs like you are, keep doing it.”

When Bart entered his own dressing room the first night, in the corner was a Gibson J45, his dream machine, a replica of Hank Williams’. Bart wanted to cry.

“Rock walked in and he says, ‘It’s yours, man.’” Bart recalls. “He told me there had only been three of them in all of Detroit, and that the damn thing had cost $3,100, but they’d given him an entertainer’s discount, for $2,600. We laughed.”

Rock knew putting this unknown country singer with nothing but a guitar out in front of his brood was a crapshoot. He suggested Bart play a couple of covers first to get their attention, and then play some of his originals.

“But I’d written 28 Days,” Bart says, referring to a detox ballad about rehab for a 30 Vicodin-a-day habit. “And I told Rock, ‘I got this song I just wrote and it’s real good – I gotta play it,’ and Rock said no, not unless he heard it first, but Brett and me talked him into it.”

The 30,000-strong audience, more accustomed to rap-rock than country, stretched out before Bart as he sat on the stool. Ignoring Rock’s advice, he started out his set with one of his originals, Hell Yeah I’m Country, and the crowd went mad.

“I couldn’t believe that feeling,” Bart says.

For the next 15 minutes, he played all originals and, unbeknownst to Bart, Rock, surrounded by his Indian Outlaw security brutes, had gone out into the crowd – standing on a crate for a better view. Bart ended his set with 28 Daysand he was rewarded with a standing ovation.

“That was a major moment, in from of 30,000 of Rock’s fans who loved me,” Bart says. “It had been a long time coming, but I thought if I can do it here, by God, I can do it, I can make it. It was proof.”

Rock met him in his dressing room afterwards, saying, “28 Days, baby, you got it!”

Back home, Bart’s high didn’t last. Five days after Detroit, Kristie left him. Sick of the drugs, the ego – scared of what his future was doing to him, to them – she ran off with the babies. Bart bought enough meth for a week, and he and Brett holed up in a Valdosta hotel.

On a tip – some say by his angry wife or a jealous friend – cops kicked the door in and hauled them off to jail for possession with intent to distribute. His growing celebrity status was causing the grim spotlight of the law to blast as brightly as stage lights.

With a show to open for Rock the next night in Kentucky, they bonded out in the morning.

“Bart was a mess,” Brett said. “I told him, ‘You’re doing this show, dammit.’”

Bart, crushed and heartbroken, didn’t care, but Brett did. He got his brother to Kentucky in time and “literally had to prop him up on the stool on stage and put the guitar in his hands,” says Brett. “I didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Bart blew them away again. He could sing – might be late, dead, but by god he could sing.

“There aren’t many people I’ve seen who can sit down with a guitar and sing a song they wrote and blow somebody away,” says Kid Rock. “And that’s what I’ve seen with this kid, no matter where I’ve taken him. I’ve had him open with me in Louisville, and Detroit, other odd places, just him and a guitar on a stool with a piano, and he’s blowing these people away. And it’s kind of amazing to step in front of my crowd and be able to do that.”

Money came and went fast. Big deals full of promise dangled like a carrot and Bart was a hungry fucking rabbit. As it became harder and harder to keep the bills paid, and eviction notices loomed, the boys moved to Houston County in Middle Georgia near their father – a born-again Christian who’d distanced himself as Bret and Bart descended into their wayward lives. He’d bought them a big pretty house in a fancy subdivision, but instead of straightening up, their addiction for meth grew stronger.

“My habit had gotten so big I knew I needed to learn how to make it myself,” says Bart, and a nearby cook showed him the ropes. Then he hit the Internet, studying for months to hone his craft. He got good. “When I started cooking it, I never ran out. I could get it as easy as turning on a water tap,” says Bart. “I had my high tweaked to perfection. I could always feel the way I wanted. Elvis couldn’t have done better.”

Bart would cook dope in the basement of the big house, keeping Downy dryer sheets spinning 24/7 to mask the pungent offal from his secret lab. But this utopia didn’t last. Caught buying too many cold pills at a Kroger supermarket on December 21, 2002, Houston County officers discovered a duffel bag full of more pills, a briefcase full of meth, and an assortment of items used in a typical lab set-up, such as fish aquarium pumps and tubing used to “blow” the dope in its final stages. Bart was arrested.

Their father got pissed, sent them packing to the backwoods of Southern Georgia, an area known for its growing meth trade. But Nashville, Rock, and a bevy of record labels such as Warner Bros., unaware and unconcerned about anything but the music, continued a heavy petting session with Bart.

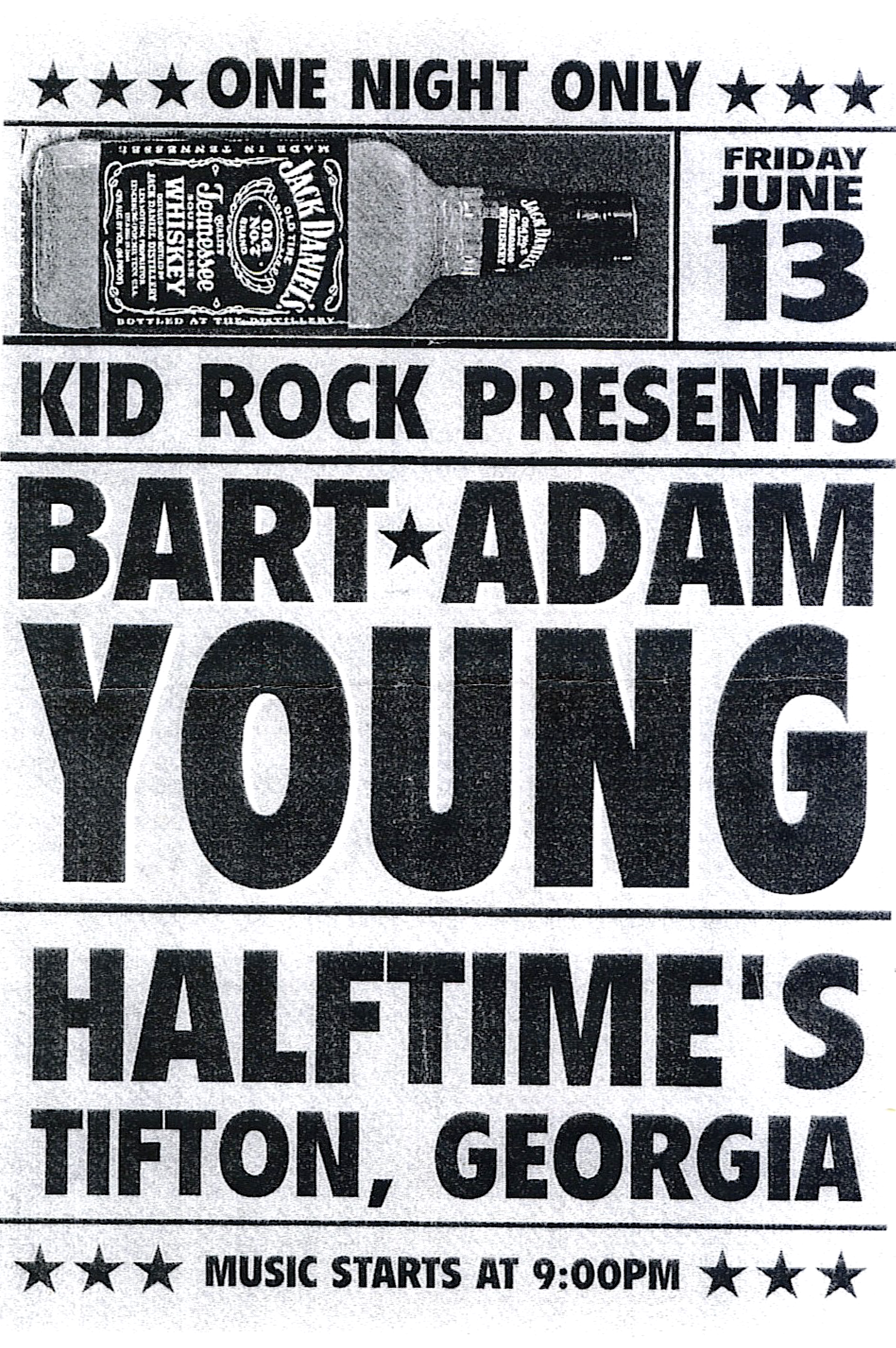

Rock went so far as to commit to flying down in June 2003 to play a show with Bart at a Valdosta juke joint called Rick’s. Through word-of-mouth, the place packed out. Rock sat on stage with Bart for a few songs and the local crowd, who might have had their doubts about Bart’s boasting, finally believed.

Rock next invited Bart to play at KZLA, a country radio station popular in LA, alongside himself, LeAnn Rimes, Trick Pony, and Kenny Wayne Shepherd, as well as then-girlfriend Pamela Anderson’s Malibu birthday party and Rock’s private birthday down in Puerto Rico.

All the while, drug agents, sheriffs, and cops, mostly from the area, were watching closely. All eyes were on the Young boys and their growing entourage of hustlers, groupies, and wannabes hoping to get a little gleam from the sparkling dazzle that seemed to follow Bart around now. In a small town, it’s not hard to get noticed for that.

+++

The compulsive behaviors that Bart exhibited as a result of his chronic meth use were all too evident, and Rock’s patience began to wear thin. Rock and Bart began to have issues – over Bart’s lack of professionalism, his vacillating between label offers (Rock made it clear that moving to a label sans Rock wasn’t going to make Rock a happy boy), and money.

“I was smoking an eight-ball of meth a day, along with 30 Vicodin (10 a handful) and at least 10 Xanax daily, everyday, for two years. “Traveling with that kind of dope meant I’d miss a lot of flights, packing, re-packing, putting an ounce of dope into emptied out ginseng capsules, stashing the rest, my personal, in my crotch. Yeah, it held me up.”

But Bart kept at it, going up to Nashville to meet with Creative Artists Agency (CAA) super-agent Stan Barnett, Trick Pony’s main squeeze. Reunited for the umpteenth time, Kristie, driving him in a rental car, got pulled over en routefor speeding and Bart, in possession of meth, got busted again. Kristie had convinced the bondsman to take Bart’s Gibson J45 in exchange for the bail, which took months to finally get back.

“You better cowboy up,” Kristie told him, “Because if you don’t meet this guy, I’m leaving you.” He made it, late, drugless, broke, and with no guitar. Barnett let him use the red-white-and-blue six-string Buck Owens had given him, and Bart stole his heart.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Barnett says. “I was thinking to myself, my God, this man’s one of the best singers I’ve heard in my life. What Bart’s got ain’t something somebody gave him, it’s something born there.” Barnett got so excited he signed Bart with CAA, even though Bart didn’t have a label, something that had never happened in the history of the chi-chi agency.

Even Merle Kilgore, Hank Williams, Jr’s personal manager of 16 years –known for writing Ring of Fire for Johnny Cash – had done the same thing. Bart sat on his office couch and started playing, and he jumped up, “You got it, kid!” screaming for his secretary to get Mercury Records on the phone. “You got it!”

Kilgore picked up a copy of Spin, which happened to have Kid Rock on the cover, and said, “son, you gotta believe you’re worthy to be on the cover of this magazine to be a star,” to which Bart said, “Hell, I’ve been wonderin’ why I ain’t already.”

Kilgore had pulled out his personal checkbook and given Bart an “undisclosed amount,” saying, “I haven’t done this since the ‘70s, for Billy Joe Shaver.”

Not long after that, Kristie left again – this time for good. Bart straightened up, “for a second,” but couldn’t keep it together. Broke, with no drugs, knowing the end was near, he holed up in the back bedroom of family friend Al Sumner’s old trailer.

One cold Saturday night, on January 29, 2005, a swarm of sheriffs and drug agents, looking for one of Bart’s cohorts (Travis Crawford) for outstanding warrants, fell upon the Cook County cotton patch and busted in the trailer. They didn’t find Crawford, but they did find three meth labs and one special lab set up to make anhydrous ammonia (the magic ingredient in meth at the time) on the property behind the trailer. Sumner, Bart, and several other men present were arrested for manufacturing and distributing methamphetamine.

Bart knows he overdid it.

“I ain’t never done anything half-ass,” Bart says. “It caused me to lose my family, I know that, and depending on those charges, it could ruin my career.”

Though Bart’s future remains uncertain, his supporters haven’t forgotten him. Homemade burnt CDs of his music circulate among vigilant fans, and these fans are true blue.

Stan Barnett, after finding out about Bart’s recent charges, speculated that this could be the very thing to save his life and career, although he flinched at the thought of focusing of Bart’s downward spiral – even though he admitted that country music had been born from this very premise.

Heavy-hitting producers Paul Worley of Warner Bros. Records, whose artists include Big and Rich, upon hearing of Bart’s legal entanglements, shook his head and sighed. “He’s got an amazing talent, a great voice, and a lot of ability, and I really see and appreciate that,” says Worley. “I really like him and his brother and we talked about doing something together. My hope is that he will get it together, come to grips with his demons, and get his music out. Being an artist is a lot of hard work, and you’ve gotta be clear-minded to do the work.”

While Bart waits, Brett is pursuing a career in gospel music, putting his own demons behind. He’s finding his own voice and direction, and says, “I’m always gonna be Bart’s brother.”

But now, both realize that their paths must fork.

Though Rock has distanced himself since the two last met in Detroit in late 2004 to record a duet (which didn’t happen due to head-butting over contracts), he keeps in touch through Brett, wanting to see Bart prove himself through time.

“He’s got to learn to be professional,” Rock comments. “That’s how the business works.”

Bart strums on, fantasizing about the concert he’s going to give when he gets out. ‘Where gonna be a show like you never seen,” Bart declares, knowing that he’s just treading water, standing still, until a slot opens in a detention center when he will serve his mandatory 12-month sentence for the Houston County charges, for which he was sentenced shortly after being arrested in January. The $175,000 bond for the pending Cook County charges prevented him from bailing out. He’d rather sit tight than ask for favors.

+++

“I ‘bout got y’all caught up, I reckon,” Bart tells the quiet men in Cellbock B. “So now I’ll play you a song I wrote, right at the end of my worst time, probably three days old about the time I wrote it. It’s called, Slow My Roll, and if I’d listened to the damn thing, I probably wouldn’t be up here with y’all.” Laughter.

They’ve been waiting.

Watching rain roll down the window

After being up three days

I ain’t seen the sunshine

I guess it’s okay

I think it’s time I realize

What I already know

I’ve been running like hell most my life

I think it’s time I slowed my roll.

I’m trying to do better, Lord

Which way should I go?

I’m a grown man and I’m down here on my knees

Will you help me slow my roll?

“Alright, you sorry motherfuckers, I’m going to sleep,” Bart says, turning on his side. After a moment, he lifts up on an elbow, adding loudly, “And let me tell y’all one goddam thing, if none of y’all like it, y’all can kiss my white country ass!”