Marathon Des Sade

By Robin Postell

(Originally published in Razor Magazine)

Moroccan Sahara. The oppressive heat has me sweating like a slave. The temperature gauge on the side of the Land Rove reads 120 degrees and the sun still hasn’t completed its mean parade through the day. With a 102 degree fever and a stomach as weak as a newborn’s, this is the most miserable day of my life.

The second state of the Marathon Des Sables, a 150-mile footrace through the desert, is being waged. This is war. Competitors get to know their foes well in a week out here; winds that whip and kiss, a sun that licks with a tongue of fire, fields full of rocks to bully the knees and ankles, and mountains made of glassy sand. They all conspire with the vigor of a general to conquer you.

Tornadoes of sand and wind whirl in the distance. Waves of heat gyrate up from the horizon, distorting the images of running figures. Flies pop and zap our sweaty brows as we pour over our maps, navigating the quickest way to the second stage finish. I jump from the Rover, a wave of nausea yanking my guts in knots. I secretly hope that Carolyn, the photographer shooting for Sports Illustrated, catches my bug. She is smug with her wellness. I think, “Just you wait, my friend.”

Denise, our other Rover-mate, is a British tour guide who plays den mother to the British contingent. She has already been afflicted and is almost well. She laughs at me, in between still frequent jaunts to the dunes to be sick from one end or the other.

They wait as I dry-heave in the sand. Bickering ensues over which route to take. Ali, our Moroccan driver, who speaks six languages fluently, has been smoking hash all day. From one of the local villages, he’s an ace driver, surging through the sandy waves of dunes, throwing us to and fro with glee. The hash, he insists, helps him drive better. His relentless jostling only exacerbates my nausea. He passes me a laced cigarette and says, “Feel better,” with a knowing wink.

This is what suffering is made of. Many runners have the same mystery malaise as I. “How do they do it?”

I want to cry.

As competitors are spewing in the sand, getting IVs at checkpoint tents, and then continuing to go on, bent on acquiring the redemption they believe a finish to this contest will entitle them, I think they’re all mad – you’d have to be to actually run, carrying everything you will need for an entire week in a pack on your back, through the Sahara in 100+-degree temperatures.

Hey, only another hundred miles to go. What’s a little diarrhea and puke? Small price to pay for killing yourself for a week in the Sahara, right? That cheap medal they’ll hang around your neck at the finish line has gotta be worth, what? Fifty cents? Add the ribbon, hell, maybe sixty. You paid $2,400 to enter this thing. That’s not including the money spent on training, time off from work for a couple of weeks, and travel to get over here. Chances of you winning: slim to none. You’ve got nearly 600 race mates to best, and trust me, unless you’re made of balsa wood and paper (or jet fuel), you ain’t crossing that finish line before Mohamad and Lahcen Ahansal, the two dusty Sahara-born boys from the tiny sand-swept village Zagora. Whichever one crosses the finish first will win 30,000 French francs ($4,500 US). For a Sahara boy, that’s about three years’ salary – a big, juicy carrot for them to chase.

So, why does everyone else do it? You won’t get a straight answer. An unspoken reasoning threads itself throughout the field of competitors. Once they finish, they’ll hold the secret and won’t tell you what it is. Attempts will be made, but they’ll have a look in their eyes that wasn’t there before; they’ll tell you if you want to know, try it yourself. That’s the only way to grasp it fully.

It’s easy to get sanctimonious upon completion of such horrific feats. They earn the right to be smug, we in the Land Rover decide. Amongst journalists, the topic of choice is always, why? Like looking at an abstract painting, each viewer interprets it differently. The question becomes rhetorical.

STAGE TWO

The six-stage, seven-day race consists of a plethora of agonies. Stage One teases everyone with a mere 15.6 miles, but today’s Dune Day is what everyone has been dreading. “I feel if we get through Dune Day,” Holly Hollenbeck from San Francisco says, “We’ll be okay.” She’s running on torn ligaments.

But there is really no hump day. Every extra day might mean fewer miles, but added problems. Unlike typical marathons, when you hit a stride and just go for it, this race is varied. Dunes, rocks, hills, dried lake beds, the occasional village – once you get accustomed to one setting, it changes.

“There is no stride,” says 40-something Cathy Tibbets, an MS veteran who runs ultraruns (100+ miles nonstop) an competes in Eco-Challenges for fun when she’s not practicing optometry in Arizona.

The physical rigors one must inevitably endure from attempting such a venture should not go without mention. Hollywood-worthy blisters; duct-tape covered, Astroglide-slicked crotch rot; nipple-rash from nylon backpack straps; broken bones; heat stroke and all its relatives; prolapsed uterus (meaning it actually falls out); gangrene; dehydration, hunger, and sleep deprivation; and even death. One competitor, a healthy 24-year-old man, became dehydrated, slipped into shock and suffered a fatal heart attack.

The race continued.

The bone-dry Sahara, ironically once the bottom of the ocean, is no place to hold a race. Nonetheless, a race has been held here every spring for over twenty years. During this time, the Marathon des Sables has grown and prospered. With one Frenchman’s solo sojourn into the desert to test his will, to this year’s nearly 600 competitor field with 30 countries represented, the race was born.

In December 1984, 28-year-old Patrick Bauer, then a photographer in Troyes, France, decided to talk across the desert. He chose a 350+ kilometer course between the Saharan villages of Tamanrasset in Algiers, and In Geuzam, the last Algerian town located a few kilometers from the Niger.

All he would take along for the journey would be walking shoes and a backpack containing a sleeping bag, water tank, and food. According to race lore, he saw a shooting star while lying exhausted in the sand and came up with the idea for the race.

The first Marathon Des Sables, in 1987, attracted only 23 competitors, with the course stretching between the villages of Zagora and Mhamid. Steadily, the field of competitors grew with every year as sponsorship broadened and word of mouth about the race spread to adventurers and sportsmen all over the world.

Today, the Marathon Des Sables is a rare trophy, a real mark of manhood. The challenge makes babies out of men, and men out of babies. Ages of competitors race from 16 to 80. More spiritual inquisition than innocuous athletic contest, the race asks a lot and gives nothing tangible in return.

The true goal of this race is not to reward you for beating everyone else to the finish, but rather to wrestle doubt, fear, temptation, anger, hunger, and even death, out of making you throw in the towel.

Most competitors entertain nearly constant thoughts of quitting. To continue hurts. But what hurts worse is to stop and know they’ve failed. Only those in the very front – those that don’t stop or seem to have the need for food, sleep, or comfort – know the meaning of this race in the true sense of the word “race.”

There are three races within the Marathon Des Sables. At the very front are those who are trying to actually win.

The middle of the race is comprised of competitors who know they can’t win but are definitely watching the clock and shooting for their highest times possible.

The others just want to finish, and prove to themselves they can do it. If they finish last along with the ever-present camels, who trail behind the race – no matter.

They finished. And what stories they’ll have for cocktail parties and at Starbucks over good and deep coffee chats.

“I knew I was making good time and getting close to the front when everyone around me started getting skinnier,” Mark Spangler from Minnesota says.

At the end of Dune Day, seven people have dropped out. Joe Girard, a Canadian police officer, lumbers his way back to his tent. “Where is the race director?” he says deliriously. “We have a bone to pick with him. Those dunes were demoralizing. I was in the Airborne for 20 years and it didn’t come close to this level of difficulty. This was incredible.”

Girard gingerly unties his shoes and quips, “The agony of da feet…I just couldn’t quit stopping…I could see the bivouac, but, I kept stopping like a dead battery.”

Everyone appears shell-shocked.

“It’s always hard,” Spangler adds, who had by yesterday’s close accumulated 15 blisters. “It always feels like something is wrong. It’s always hot…uncomfortable.”

STAGE THREE

Sandstorms abound on the third leg, stretching 23.75 miles. Runners wear turbans and goggles and lean into the wind. My fever has dropped a degree but I’m shivering and sweating with equal vigor. Carolyn looks on with quiet disgust. I wait for her inevitable doom.

From the first day of the race, competitors begin to drop out, but today, the toll rises. Compounded injuries, lack of water, and dysentery all combine to form a perfect recipe of torment. Often, those who you expect to do well fail miserably – and vice versa.

An often overlooked factor that makes the MDS worth enduring is its sense of family. A mini-UN of sorts, competitors come from all walks of life, all social strata and economic brackets, religious and political creeds, every imaginable educational background, and countries on every continent. One woman, Lisa Berry came directly from Antarctica where she had spent the summer driving an ice tractor.

At any given race, you will witness the gamut of humanity. During five years of my coverage of the race, I’ve met cocky investment bankers from Manhattan, two of which wound up in wheelchairs at the post-race bash with vicious cases of gangrene.

Another, a Roman mounted police officer and an Olympic pentathlon gold medalist, was lost in a sandstorm in 1994 for eight days, drank his urine, sucked the blood out of a bat, tried to commit suicide with a knife, burnt his backpack to signal helicopters, and was finally rescued by Algerian soldiers when he wandered over the country’s borders 44 pounds lighter. But, he’s back this year.

A team of San Miguel reps from Spin carrying heavy backs full of sausages and martini shakers (who, of course, proudly came in dead last).

Another team of cigarette-smoking French Foreign Legoinnaires stationed in Djibouti had come and refused to speak to anyone else but me because I was working at the time for Soldier of Fortune magazine.

One blind Frenchman came with a guide, no small feat for either of them.

A housewife from Italy looking for something life changing found that change.

A German femme fatale with the thighs of a quarter horse managed to stay at the front of the pack even after breaking an arm.

A 70-year-old yogi from Paris meditated daily before and after each leg of the race.

A team of philanthropists from Hong Kong.

A British veteran who had lost an arm and a leg clearing landmines in Mozambique, running on a prosthetic foot, said he only had one foot to worry about blisters.

A 60-something retired contractor from San Jose, who had the unfortunate occasion to need Superglue to patch together his torn scrotum while wiping during a squat, kept me entertained throughout the race with his personal anecdotes.

A bike shop owner from Michigan.

A public defender from D.C..

A merchant mariner from Florida.

A student from Nigeria.

A team of guards from Buckingham Palace.

Two brothers from a Moroccan Sahara village.

During my coverage, I met hundreds upon hundreds of fascinating individuals, all with unique personal and professional histories, and all very personal recollections from their race experiences.

All come with their own notions about what the race will be like and how they will manage. Hardly ever does anything turn out the way they had planned. Forged bonds have a great impact on how they fare. The more people met, the larger the cheering squad. If they’re on their knees, hurling energy bar bile into a dune, his next-door tent neighbor could come along and convince him not to quit. The fellowship of journeyman keeps the race going.

Rarely do you see competition get in the way of goodwill and decency. On occasion, you hear gossip and quibbling about so-and-so’s pack being lighter than regulation; rumors that the race organization looks the other way in some cases, favoring some competitors over others.

Maybe they do – maybe not.

This is all part of the game. The Americans and Brits tend o make comments like, “That’s the French for you.”

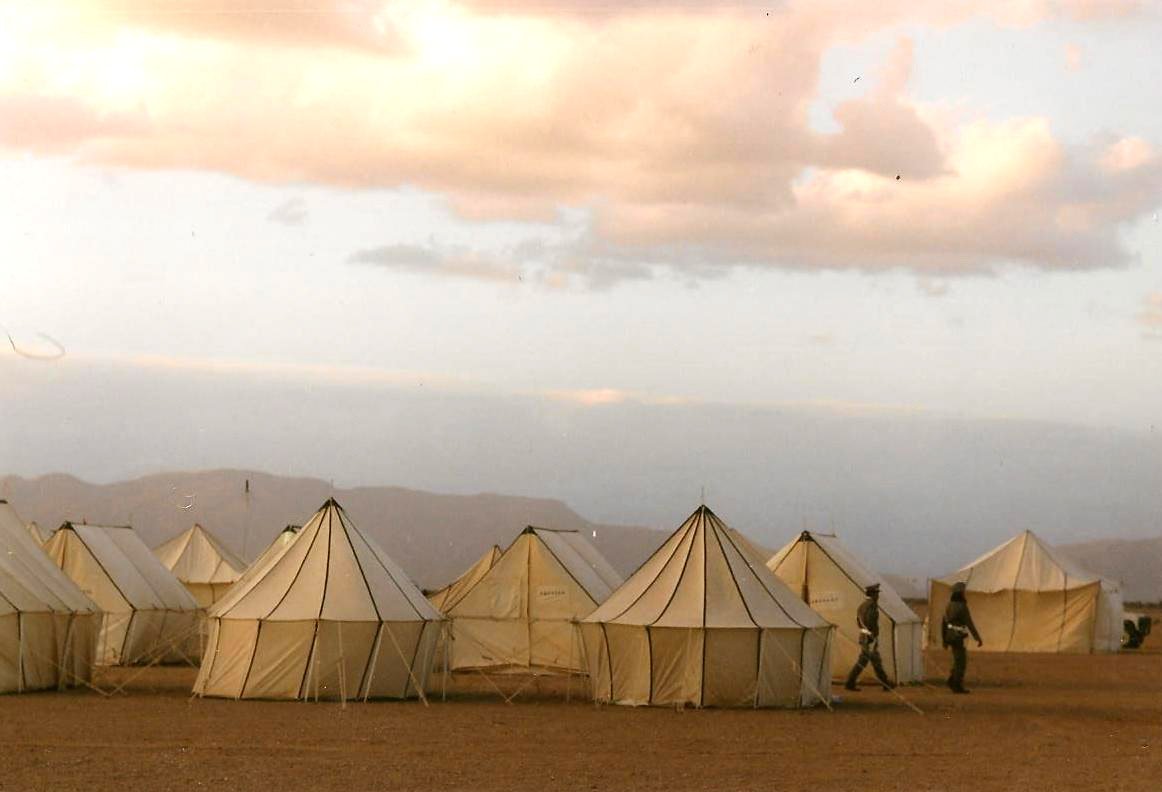

The traveling bivouac that becomes home and salvation is logistical brilliance. Desert nomads dressed in heavy robes or layered woolen garments are hired to erect it in the afternoons, then break it down and move it at daybreak. My usual wake-up call is a Bedouin tearing up one of the stakes holding down my tent. The rattling canvas strikes terror into my soul as I struggle into wakefulness and throw everything in my bag.

Racers sleep underneath black burlap open-air tents, while journalists and race personnel sleep in large white canvas tents – the difference between Motel 6 and the Hilton.

A starting line is always present at each bivouac, and a finish line quickly erected at the next bivouac at th end of each stage.

In this moving village lifelong (sometimes marriages) friendships are sparked, but as the days go on, the friendships turn familial.

There is an element that waxes military, in that the competitors develop a platoon mentality. They are essentially “in the trenches” together, and some of the strongest bonds of a lifetime spring from just such sharing of suffering and overcoming, even if they never meet again.

The ability of these ordinary people to accomplish extraordinary acts out in the Sahara can in part be traced back to these bivouac moments.

In the mornings, racers gather to discuss the coming day, sorting through the packs, exchanging advice and encouragement. And at the end of the day’s leg, they collapse in the tents (6-8 per) rehashing the leg’s horrors, lying next to one another’s sweaty bodies, stinking, aching, itching, bitching, groaning, eating (and rationing) their allotted food, and finally falling asleep (or trying to). Snores, farts, and sleep-talking are as common as blisters and crotch rot. Personal hygiene is a joke by Stage Three.

In the giant kitty litter box of the Sahara, competitors return to their ancestral roots of taking a squat. At first, modest competitors wander off until they’ve become a mere speck on the horizon in order to take a private dump, but by mid-race, competitors inch closer and closer to the bivouac and tent, modesty be damned.

The “shitting fields,” as the expanse of the desert beyond the tents become known throughout the years, becomes littered with the little tufts of wadded toilet tissue and competitors lament and accuse one another of not burying their crap.

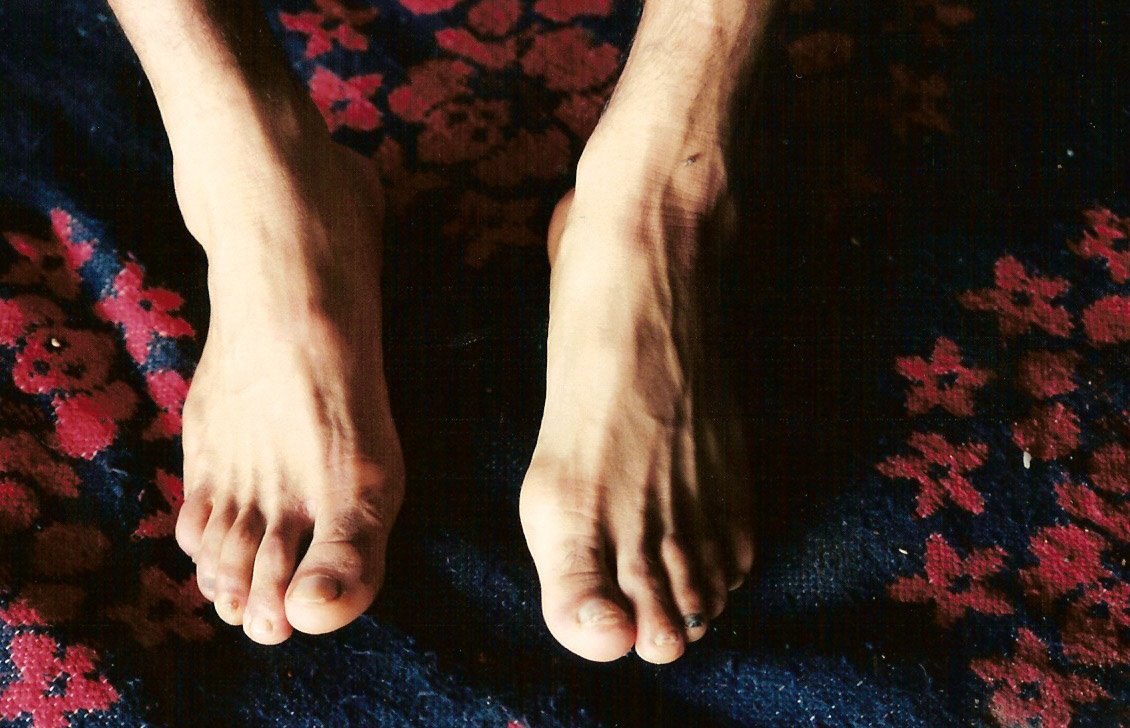

With blistered feet,

one gets lazy – take one step further than absolutely necessary seems a waste of time and effort. Everyone is reduced to delirious prepubescent chatter, ranting as the race persists, simultaneously inspired to philosophical heights never before reached.

STAGE FOUR

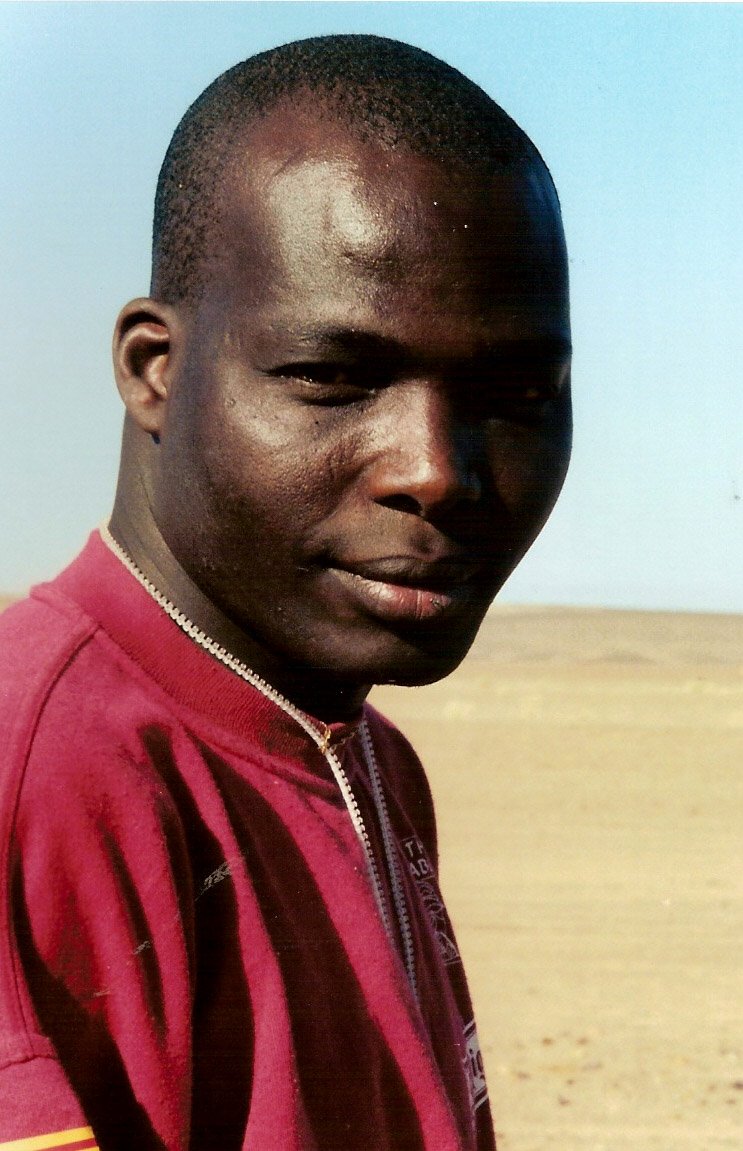

The fourth and fifth days of the race have to be the worst. At 51.25 miles, Stage Four is no cake walk. Because of its length, the leg stretches over a two-day period, although front-runners will finish in a handful of hours. Today, Lahcen Ahansal and his younger brother Mohamad, will break their previous year’s record, completing the stage in just over six hours, crossing the finish line holding hands.

For the last five years, the brothers Ahansal have dominated the race. Their humble beginnings as Saharan village boys make their achievements in the race all the more incredible. Here, in the tiny wandering kingdom of this race, they are royalty. All legs and arms and teeth, these two kings have made many worldly, weathered athletes and esthetes alike break out in goose bumps of awe.

Fellow racers idolize them and shyly stroll past their tents in hopes of catching a glimpse of them.

Their abilities seem preternatural. Kite-like, they blow across the sand and rock, averaging 10 kilometers an hour.

Close on their heels is Italian police officer Marco Gozzano, who through the years has also gained a near-celeb reputation in the race. Over 50, along with Frenchman Gilles Diehl, are always in the front pack. They return every year.

As night falls and the winds cool, competitors continue to cross the Stage Four finish. I’m feeling better, but still weak. Carolyn, about mid-afternoon, begins to get a pinched look on her face. She’s lying prone in our tent with her hand on her head. I feign sympathy and give her some anti-nausea tablets.

Simple joys.

I wander to the racers’ tent village. Jason Walker from Minnesota, a hardcore party animal on the club circuit back home, has been comic relief.

“I was thinking about ice cubes until about six hours ago, and then all I wanted was a hug,” he says, managing a laugh as he heads to the haven of his tent.

Those left on the course will endure frigid night air. Some will sprawl on the sand, opting for sleep and a morning finish.

Others will slog on.

The distant glow of the bivouac beacon will serve as both inspiration and disillusionment to those wandering through the night, as it never seems to draw nearer.

For many, this is a sad, awful time they will never forget.

By the end of Stage Four, 57 have withdrawn. Tomorrow, marathon day.

STAGE FIVE

I’m keeping food down and Carolyn is not. She’s so sick that I almost feel sorry for her, but I remember her apathy and quietly titter when I walk away from the tent.

By now, everyone knows the end is possible. Marathon Day, 26.2 miles, is not easy, but it means they are that much closer to a taste of what life was like before this week started.

“I can’t believe it,” says Larry Brede. “In 48 hours I’ll have a shower, clean clothes, food, and as much beer as I can stand. Isn’t that great? Clean and drunk.”

Today’s heat is the worst. Black flies busily annoy everyone. The heat grinds its heel into your back until you collapse and wait for it to grow bored with you and leave. If you’re sick, you’re sicker.

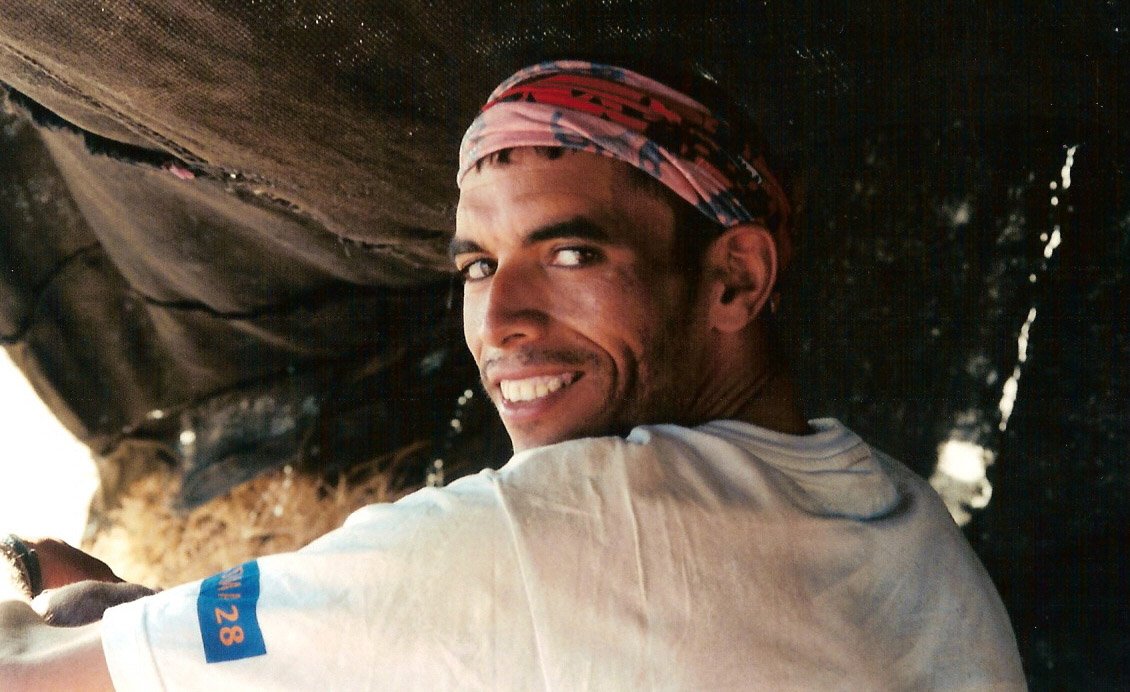

The Ahansals are still managing to keep their lead. Mohamad crossed the finish line first, his knotty feet bare as he lies on the rug of his tent and smiles for photos. His toes splay out to explose nothing but parched skin, no blisters. He and his brother are mountain guides in the Atlas region of Morocco. He says that they use their winnings for building their own guide business.

They bought their mother jewelry with their first win.

Mohamad tells me about Lahcen lounging in his robes one day years ago in Zagora.

“He saw the race as it came through,” Mohamad explains, “and he tears off his robes and starts running alongside the other competitors.”

Bauer was so impressed with Lahcen’s high unofficial finish that he invited him to run the next year. After a couple of tries, he won. And hasn’t stopped.

Mohamad joined in and took a win as well. Mohamad tells me they learned to run fast be stealing fruit from vendor’s carts.

STAGE SIX

Done. After 13.1miles the race of their lives has wound itself out. Lahcen Ahansal takes first, with a total time of 18 hours and 42 mintes and 10 seconds. Competitors run, walk, leap, cartwheel, dance, and hobble across the finish line standing in the middle of the village. Some drop to their knees and kiss the ground.

Patrick Bauer meets each one, kissing both cheeks, draping a medal around their necks. They hassle like dogs and search rabidly for something cold, as it is usually a given to have treats waiting for their hungry, outstretched hands. They’ve been unable to accept anything from anyone for a week, and now, they’ll take hot Cokes, junk food-filled lunch packets, and rolled carpets for winners and runners-up. Mohamad and Lahcen do jigs for the crowd as Moroccan musicians surround them in dizzying exhibition.

In the end, what do they feel?

Probably much like Bauer did in 1984. The whole process will take weeks, months, for their bodies to heal. The reality of having finished the race will take much longer to sink in.

To cleanse the soul, add a blend of suffering, bake in the sun in an oven of sand, then sweat it all out; all that damned trauma of civilization and all the bastard thoughts of contentment that diaper our tempered spirits ad make u s fat and indolent and oftentimes quietly miserable, slip into the sands and leave you new.

Reborn.

At least for a little while.

Until you return to your aid-conditioned nightmares, let a couple of weeks pass, and start tallying up your credit card debts all over again.

Back home, to worlds of plastic and fiberglass, hot and cold water, automatic ice cubes and commodes that flush without touching them, to bed covered in waffles of puff and pillows of down, to video games and cell phones and computers and cable TV. Back to your own private dins of iniquity, back to acquiring things instead of peace of mind, until it all needs purging again.

Which explains why you see so many of the same faces here, year after year.