TO BEG, STEAL OR BORROW: Homeless in NYC

By Robin Postell

All images are a copyright of robinpostell.com, and may only be used with permission.

Dirty New York raindrops pock mark the smooth surface of the milkshake. I cup a hand over it and trot towards Columbus Circle. The paper-sacked bottle of vodka digs into my right armpit; a pint full of promise for a man whose home is in his shoes.

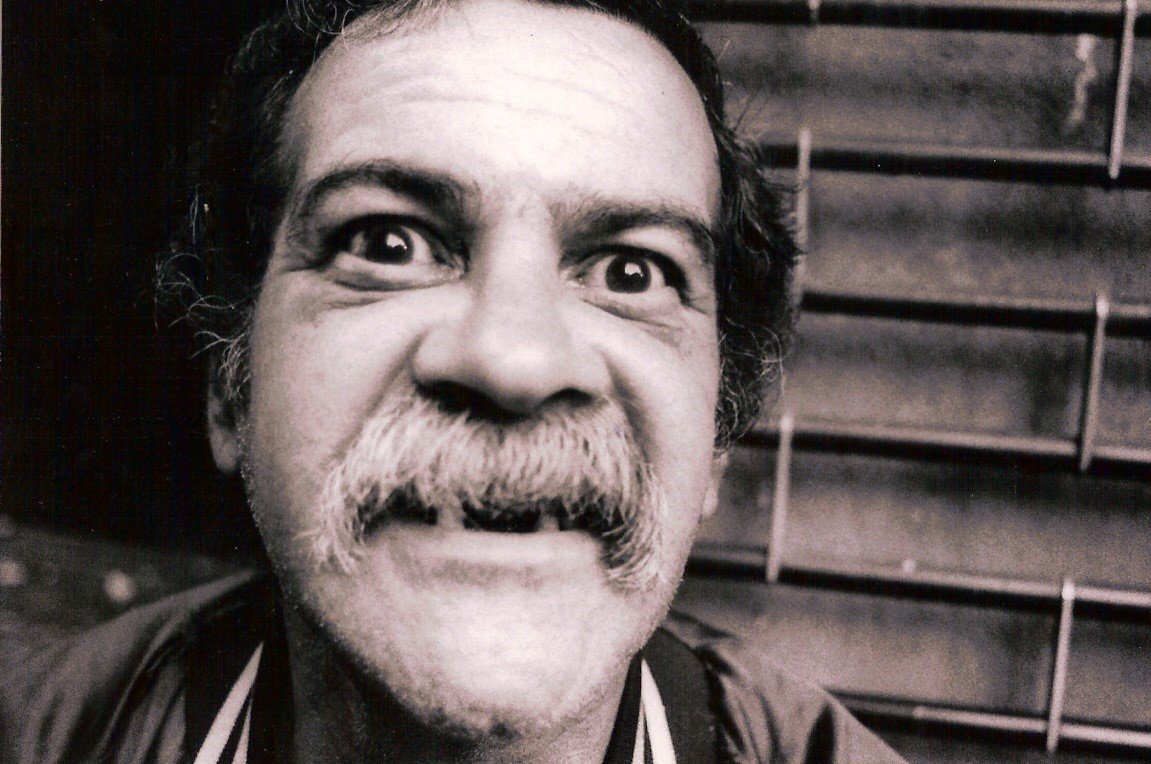

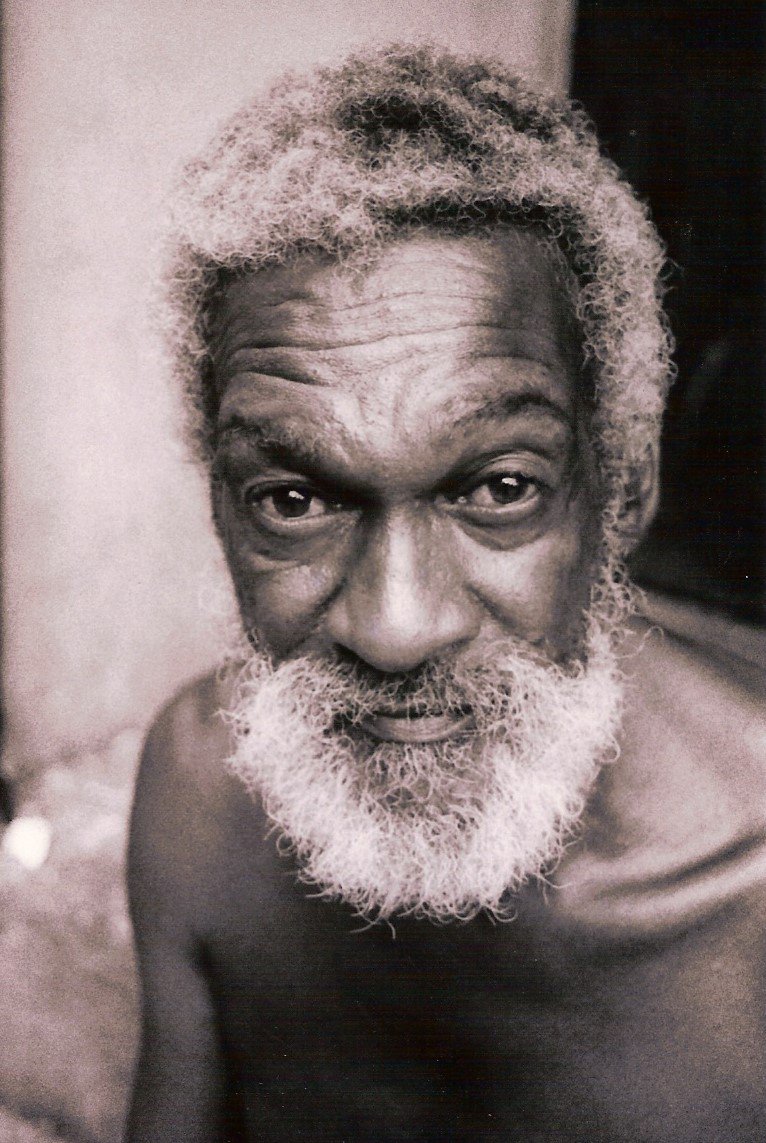

When I reach 59th street I spot Jesus’ little camp on the Circle, comprised of two industrial-sized laundry baskets full of soiled clothing and collected junk, decorated with half a dozen American flags and sheltered by three umbrellas in various hues. Several jackets and two baseball caps stacked over his oily gun-metal gray locks keep him dry.

Lost in reverie, his memory reboots upon sighting me. His rotten-toothed grin spreads, along with his arms. Jesus chuckles low and hard in absolute, unabashed glory. Spotting the milkshake he shudders visibly with joy - but seeing the vodka causes him to gasp and boom with baritone luster what sound like Spanish prayers. “Oh my darling,” he sings, stopping to embrace first me, then the bottle.

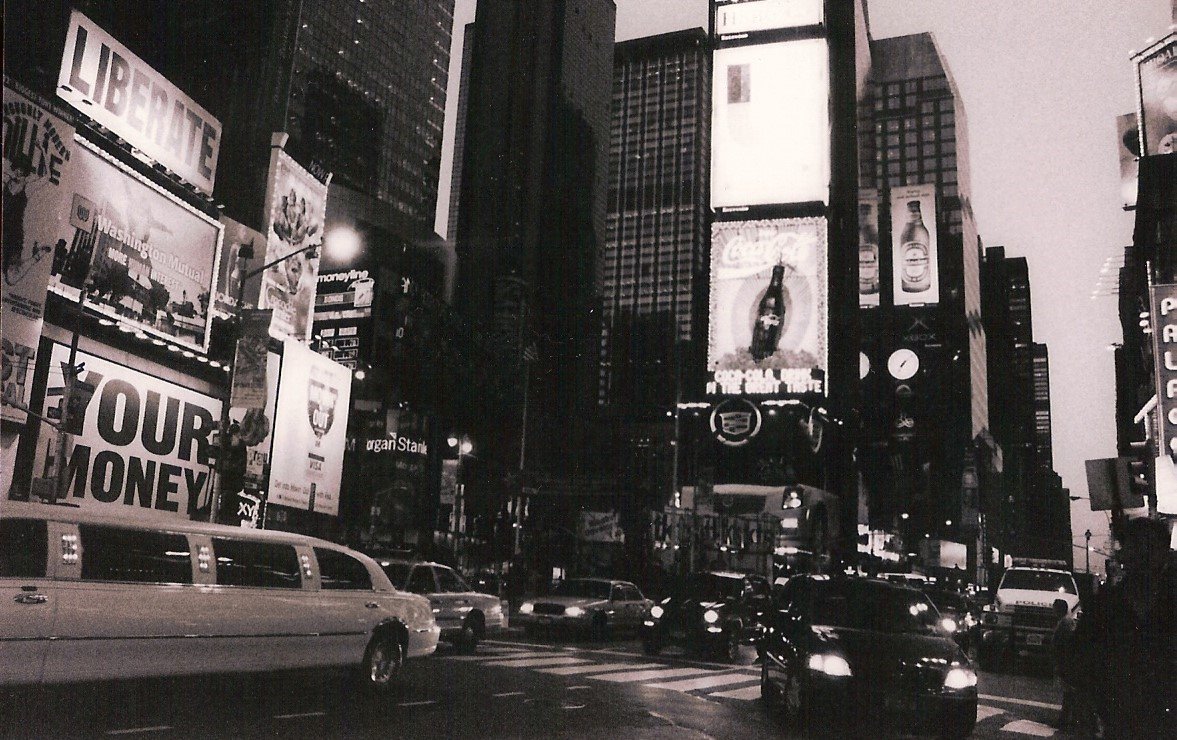

Jesus Guzman is one of thousands of homeless people living in New York City. The Coalition for the Homeless (COH) estimates that each year 100,000 New Yorkers experience homelessness; roughly 32,000 sleeps in the shelter system, while thousands more, like Jesus, prefer the streets. He is an anomaly here in a place where great wealth practically steams from the gutters. Ostentatious symbols of success and glory surround him, while he, in stark contrast, is a perfect example of prosperity’s cruel flip-side.

Most of the time, Jesus is ignored, but that’s to be expected. You don’t make it in the homeless grind if you’re thin-skinned. Vodka makes it thicker. The cops have let Jesus maintain his camp for the last couple of months because he sweeps the high-traffic area every day. Before becoming homeless this year he had an apartment, but was evicted when he lost his job as a sanitation superintendent due to his excessive drinking.

“Vodka is my vitamin,” he explains. He tells me about someone leaving a hundred dollar bill in his buggy one night while he slept. Overjoyed, he went straight to the liquor store. “The liquor store is my pharmacy,” Jesus explains. “It kills the pain. It makes me Superman.”

Feeling generous after his bounty, he took a fellow homeless buddy to eat seafood, followed by another trip to the liquor store. They spent the rest of the night full-bellied and bleary-eyed.

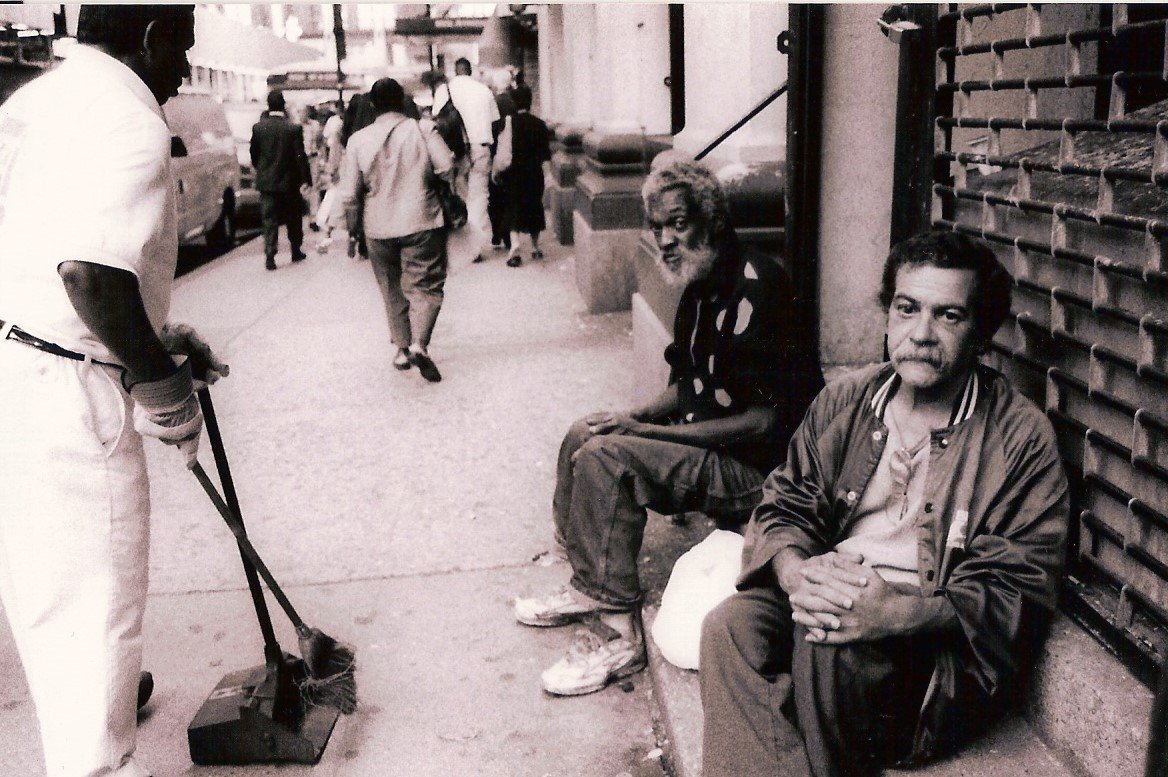

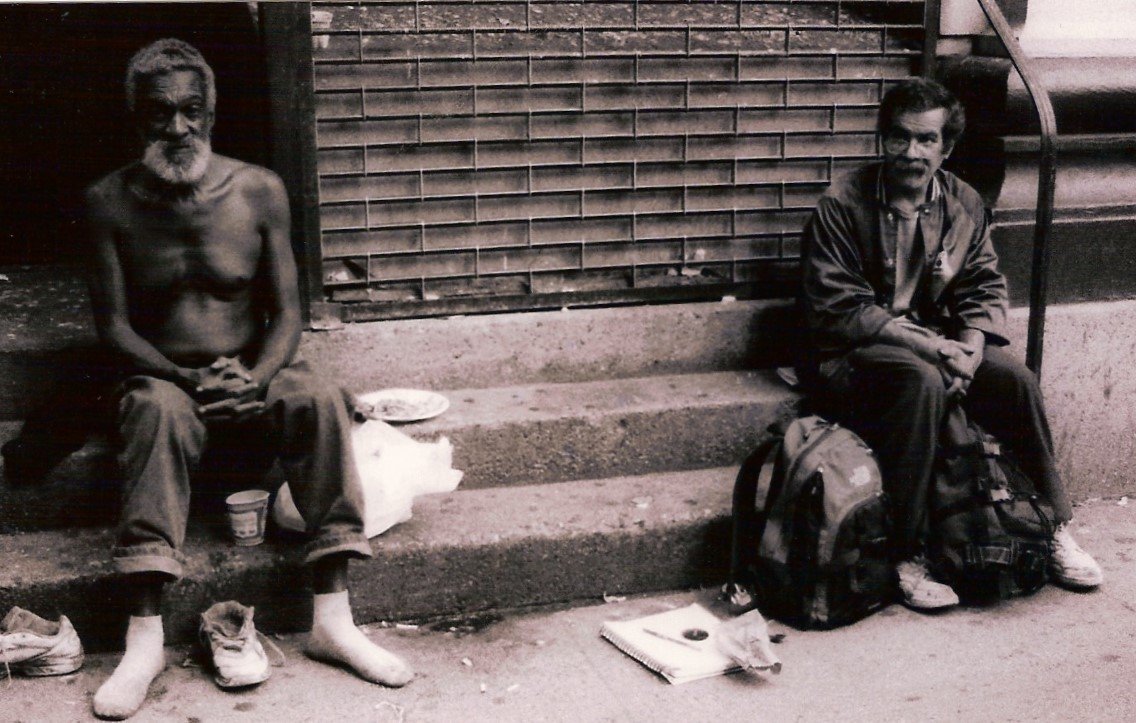

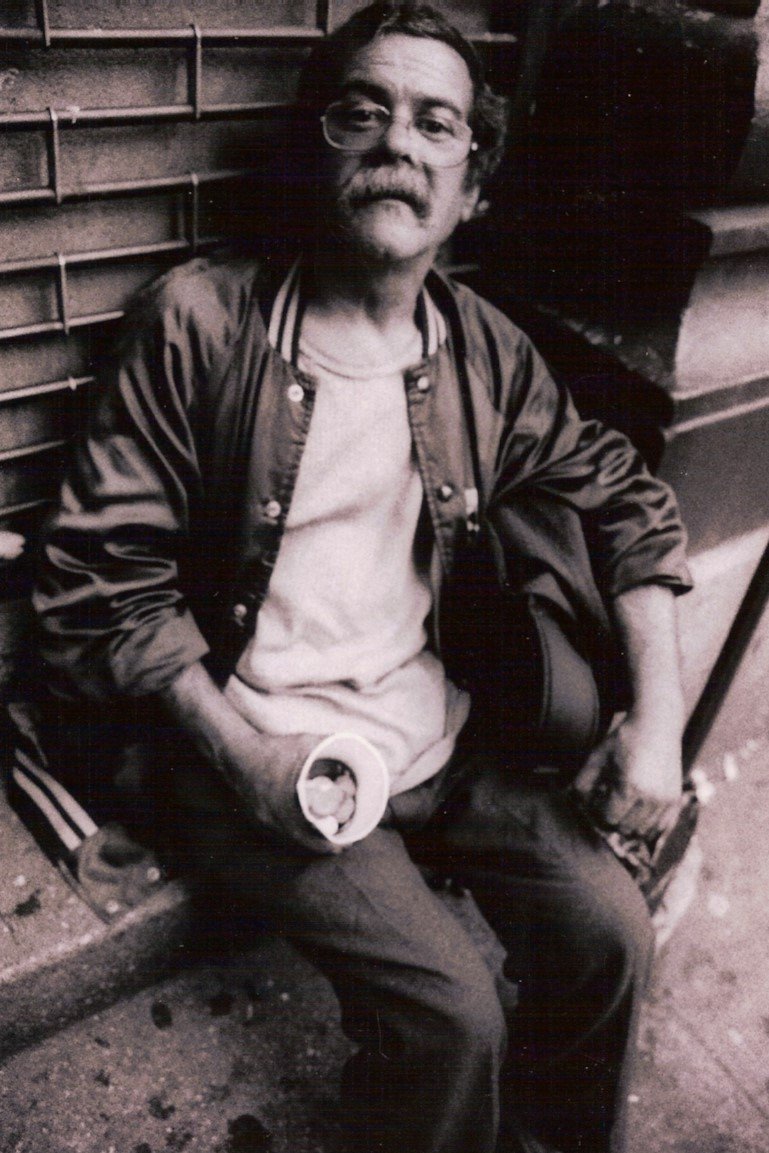

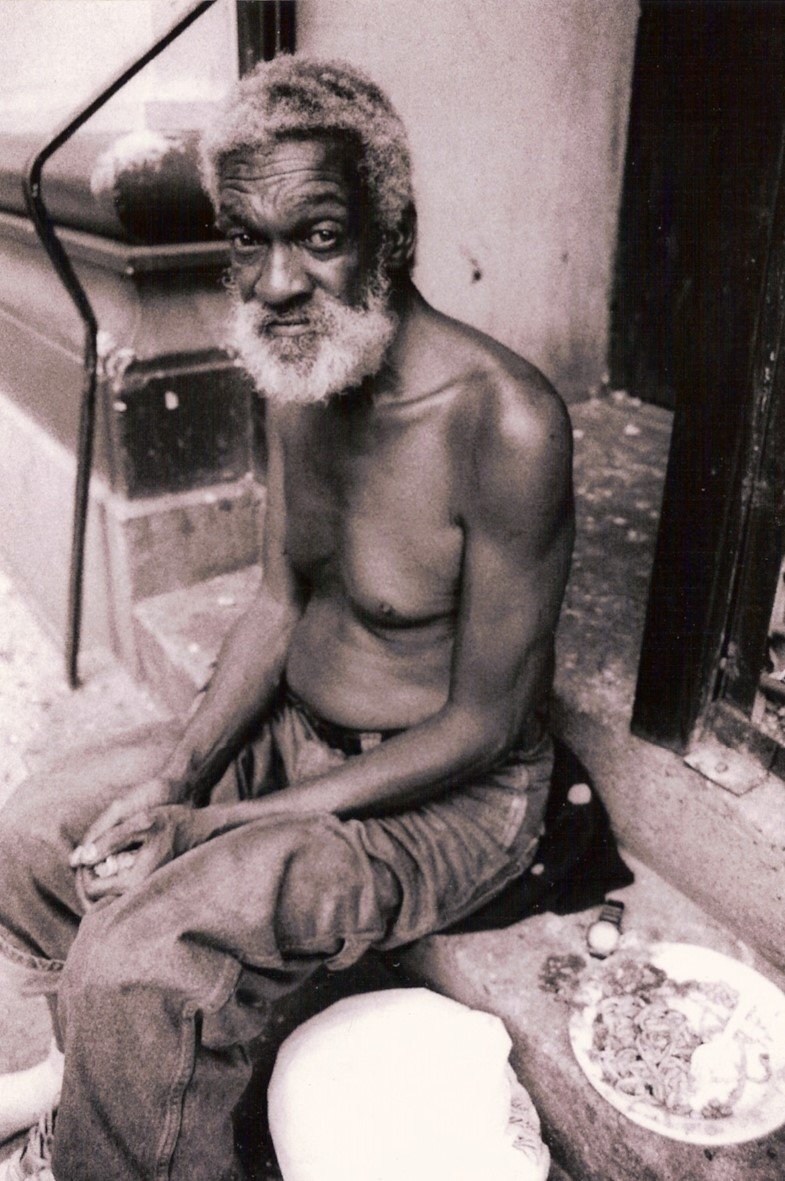

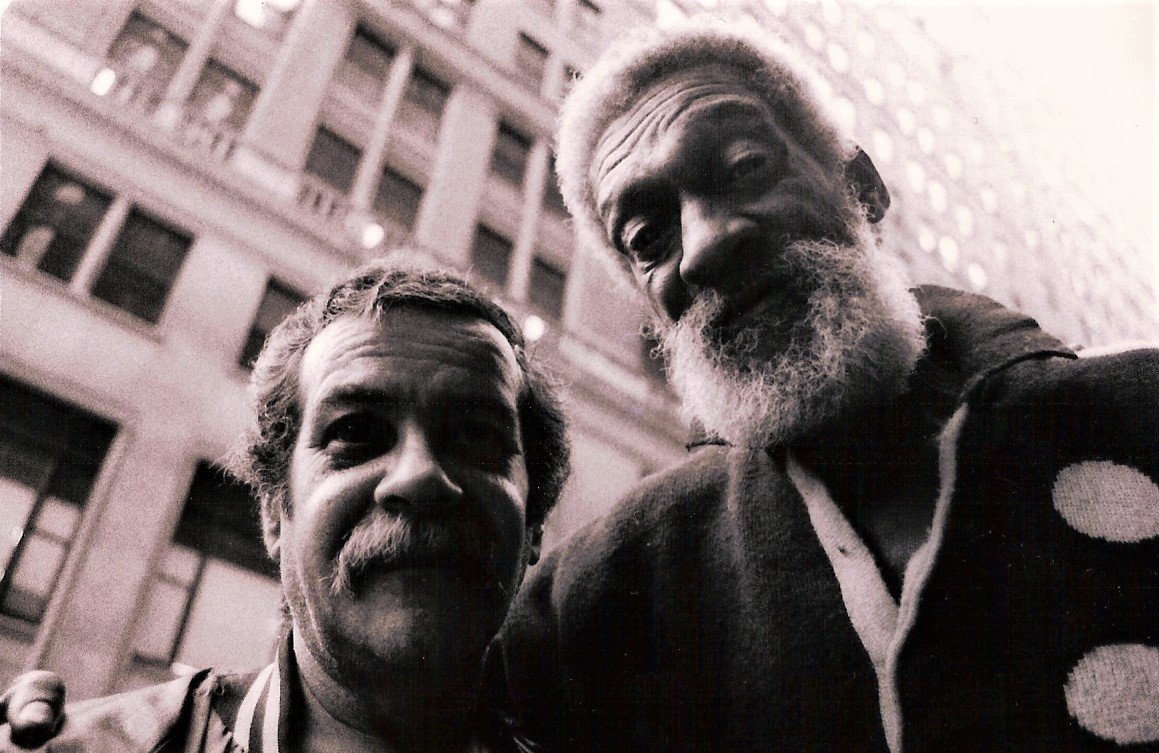

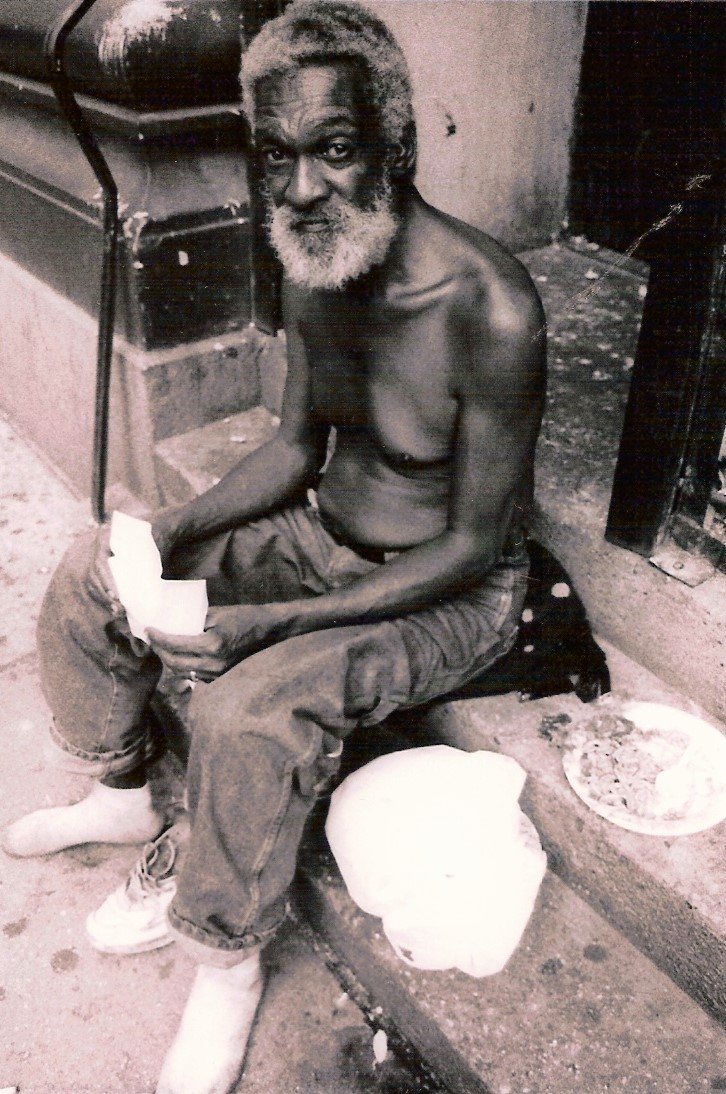

Later in the afternoon I wander downtown. The sun is shining now on New York, the steel-and-guts beast everyone loves to visit and conquer. Don Stone and Jose Soto are sitting on the steps at 32nd Street, only a block away from Penn Station and Madison Square Garden. With the Path (Port Authority Trans Hudson) station situated right around the corner, they’ve got a perfect spot for panhandling. My gifts of cash and cigarettes earn me a seat next to them on their three-step stoop, with my ass an inch away from a paper plate spattered with a gooey blob of spaghetti.

Don, shirtless, his sweater by his side, occasionally picks up the plate and shovels in a mouthful. The steps are covered with years of nasty street stains, but this is HQ. Offering me a seat, I nudge my body between the two of them and Jose picks up my Northface backpack to stash it between us and out of harm’s way. “You have to be careful, baby,” Jose says, “People are crazy out here.”

“We’re here every day,” Don, 59, says. “If you see one you’ll see the other. We’re best friends.” This is their 9-to-5 grind, how they make ends meet. As people make their way to and from work, in and out of offices and train stations, Don and Jose do their thing. They have regulars, they tell me, and plenty of others who are either indifferent or tell them angrily to get jobs. Good bad and ugly, they know them inside out.

“One lady said to me, ‘get a job, you bum,’” the bass of his voice revs and vibrates the engine of his memory, and, full throttle he continues, “I told her, ‘I got a job! Watching you!’”

Don and Jose are well acquainted with the soup kitchens and any other philanthropic effort aimed at their demographic. Don pulls out a list with every soup kitchen location and times they serve, and another with a list of shelters, listing each of their services – which usually include showers and other handy benefits. These are parts of the world they left behind and they don’t like them, avoid them the same way most avoid homelessness. There are hundreds of soup pantries, kitchens and shelters several pages long. The City of Hope (COH) reports there are over 1,000 in NYC, but still turn away 2,500 homeless every day.

Don tells his story even before I ask, saying once upon a time he’d been as normal as anybody. Growing up in Pittsburgh, he attended a little college after high school but was too busy getting drunk with his buddies to adequately apply himself and earn a degree. At 21 he opted instead for the Air Force as a way up to get somewhere. That, too, ended and he tried marriage – to a woman by the name of “Stupid Bitch,” with whom he promptly divorced. After that he moved here to NYC working various jobs and wound up marrying another woman who he also divorced.

And that’s when he became homeless, in 1978.

Don unapologetically blames women for his problems, but does concede graciously that alcohol had taken front and center as women had disappeared. He stares straight ahead at this point, into that thin-air place every introspection leads for anyone who has done something for which they feel culpable and wounded.

“I just said fuck it,” he says, throwing his hands up with a shrug. “I got sick and tired of working. I’ve been making it all right. I change clothes every day. I sit and pray in the churches, make my confessions to the priest, then go straight to the liquor store. You know what’s funny? My mother and father never drank or smoked. I was the black sheep. What happened? The devil got me, I guess.”

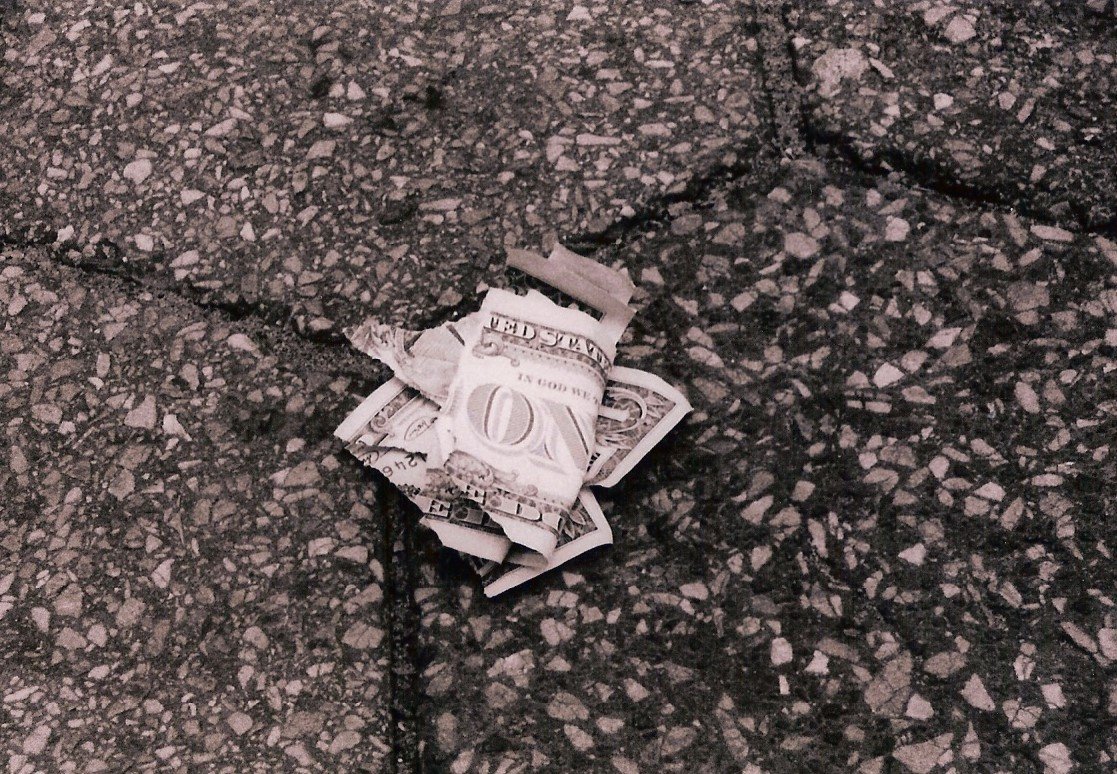

Fifth Avenue is his favorite place to crash. “People go by and say, ‘Oh that’s Pops,’ and leave a couple of dollars on my chest,” he says. “White Castle cheeseburgers and a soda for when I wake up. I know it’s not the right thing to do. I like to wake up to food, coffee, and money. And a cigarette. I don’t think that’s a lot to ask of New York City.”

“Gimme the cup while you’re talking,” Jose says to him. He hands it over, a small Dixie paper cup.

“Dump out what we already got,” Don tells him and Jose automatically pours it into a sack secreted in a mound of jacket and shirt.

Don starts begging as soon as he gets the cup in his hand. Shift change.

Jose Soto was born in San Juan 55 years ago, moving to the U.S. three years later. “I started drinking when I was 11,” Jose confesses, staring into that thin-air place, his eyes glazing if but for a second or less. By 13 he was already working to help his family, but people in the neighborhood liked him and noticed he worked hard. “I never went without a job,” he says.

One day he hollered at a pretty girl in rollers standing several stories high on her fire escape. “She blew me a kiss,” he smiles. “I fell in love.”

They got married, had kids, and Jose worked steadily, becoming a tech for an electronics company. After 7 years of dedicated service, he was given a dime raise. Jose felt the first piercing needles of indignation before the ultimate stab in 1994 when NAFTA nailed his coffin shut. His company wanted him to move to Mexico and work for $3.98 a day. His drinking worsened and he resigned not long after. The love of his life divorced him after 36 years of marriage.

“Everything started going downhill because of my drinking,” he sighs. “My wife was wonderful. I was a good husband and I gave her all my money. She’d say, ‘But you’re drunk!’ and I’d say, ‘Sorry, I’ve been drinking since I was 11 and you met me when I was drinking!”

Once a week, every month, for the last six years, Jose meets her at Penn Station and she brings him clothes and money. He’ll ask, “Can I come back?” and she’ll say, “No, you’re still drinking. When you stop drinking, you can come back.”

Jose met Don before he became homeless when he had a job at Penn Station. He’d sweep the floors, dodging the dozing bums – of which Don was one; even bringing them soup. Before long, Jose became one of them.

“They were nice to me,” Jose says matter-of-factly. “And I was nice to them.”

Don and Jose share a bond that is the sort you see in little boys; the blood-brother moment pressing slashed and bloody thumbs together clearly in their past somewhere you are certain. These are stories to me. For them, it’s who they were, and are; a testament to which I am bearing witness.

“A lot of people look at us like we’re pieces of shit,” Don says in that gravelly voice that carries all the way down the corridor of 32nd Street. “But we’re all God’s children. They don’t give a fuck. So we panhandle. Every day at 8 a.m. we’re sitting here shaking a cup. And I’m not ashamed of it. I’m not stealing. I need money just like a working man needs money.”

The largest amount Don’s ever received in one chunk is $20, Jose $10. I peel off the rest of my ones and blow them kisses as I wrap up our visit, telling them I’ll be at HASP volunteering to serve meals. They nod and smile at me, hug me, jive-talk a few good-byes, handshakes, Jose hoists my blue and black backpack that has traveled on six continents in half as many years onto my back, and say they’ll see me there. Don’s voice rumbles with a melody only sixty years of being him could produce. The whole world can hear him, I think, but he’s talking to me. What a goddam star, I think. Jose’s ear-to-ear grin reveals missing teeth that are more charming than any stellar set of pearly whites. Something about being accepted by the unaccepted elevates me; inexplicable and remarkable.

Unwashed and hard, gritty and brutal, but real and warm: alive. They have a strange, abiding happiness that normal folk seem to be missing.

HASK (Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen) is considered the most prominent soup kitchen in the city at The Church of the Holy Apostles on 296th 9th Avenue. The largest, it is one of the ways people like Don and Jose keep going. Donations from all over the world flood in to aid HASK’s struggle to assist the needy - $7,000 per day, over $2 million a year. Fire in 1991 nearly destroyed it, but the next day 990 meals were served by candlelight. Donations poured in to save the Church.

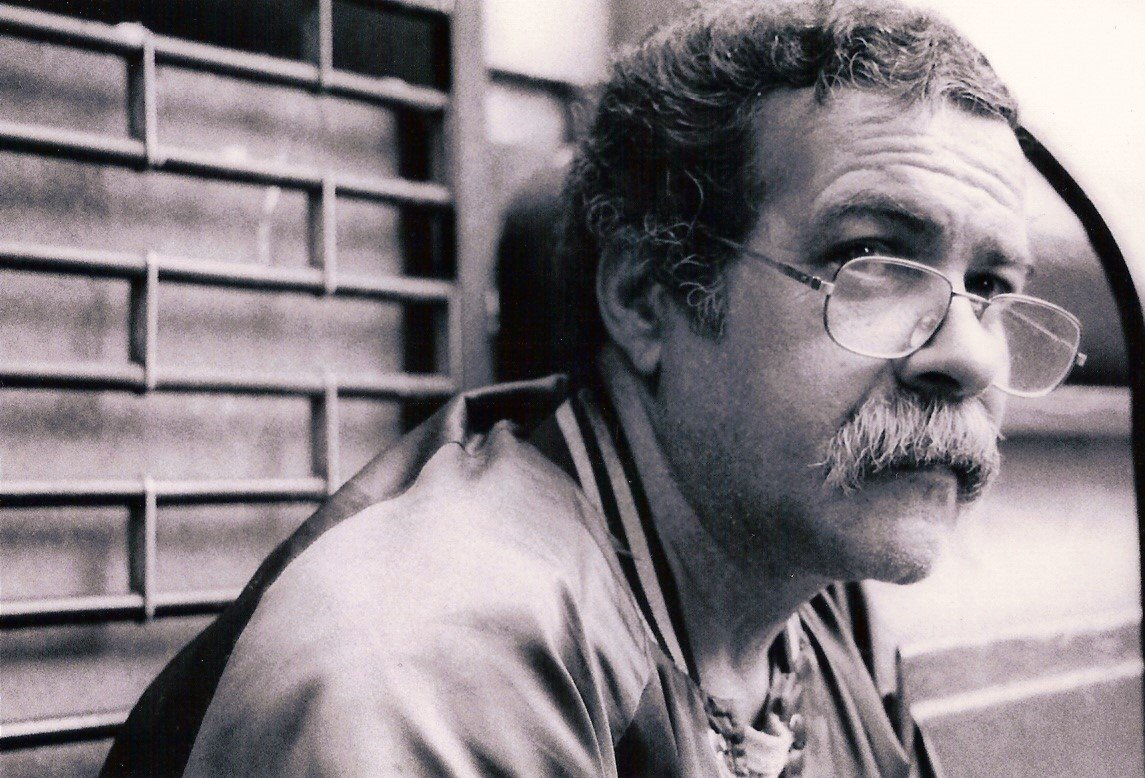

Dr. William A. Greenlaw, known fondly as Father Bill, has been around from the start, 20 years ago. An astute student of homelessness, this Duke grad was an avid anti-war activist in the 60s. HASK fulfilled his desire to “get his hands dirty” with another cause.

“Something happens that makes it fall apart for people,” Father Bill muses pensively. “It’s multi-faceted – drug and alcohol addiction, mental illness…bad luck. Helping someone is more than getting them food and housing.” Father Bill knows that a multi-tiered rehabilitation system has to be in place to make a dent in the problem.

“These people are the lowest of the low – from a socio-economical perspective,” he adds. “They’re coming from poor communities, with no role models. They feel worthless. They hang out and make babies. We’re here for energy, in hopes they’ll get off the line. Some, with a break, could. But these complex issues first must be addressed.”

In the interim the church serves an average of 1,200 meals daily between 10:30 a.m. and 1 p.m. All are welcome and the place is so popular volunteers are frequently turned away due to the overwhelming support. Today I am one of 57. Even Mayor Bloomberg volunteered on Christmas Day before his inauguration. His wife and kids still volunteer.

“Maybe it’s a little addictive,” says Barbara Neal, a regular volunteer from the Upper West Side. “I get a good feeling from doing it, then I feel guilty about feeling good about something coming from other people’s suffering. I love these people. I thought there would be so much sadness here, but it’s not like that. They’re full of piss and vinegar. I never thought about how hard it is to live in this city unless you have the means, until I volunteered here.”

Crowds gather outside the church early. Inside, volunteers and staffers organize the food lines. The sweating cooks have been stirring steaming pots and pans madly all morning. The “guests,” as they’re called, come through with their plates and head towards the church worship hall. The regular pews are pushed aside and folding tables and chairs are set out daily to accommodate.

“I’m in this for my religious faith. If it was measured by how much of a difference I was actually making, I’d run out the door screaming,” Father Bill laughs. “I do some head-scratching – what is it about this place? It’s come together remarkably. We look people in the eye, we open the door; you are our honored guest here. People who are made to feel like the scum of the earth we make feel important.”

“For every person out here on the streets willing and content to shake a cup, there are those hustling to get beyond it. Steve Riley is an example of what willpower can accomplish even when the hand you hold ain’t nothing but jokers. Today he heads the United Homeless Organization (UHO), one of the oldest grassroots organizations operating in the U.S. If you have ever set foot on a New York street, chances are you have seen one of the many folding tables with a large plastic jug and a stack of UHO pamphlets manned by a diligent attendant.”

Sixteen years ago, Riley and a friend, both homeless, looking for help through the Coalition for the Homeless (COH), came up with an idea to help people help themselves. It would provide a variety of services for homeless people, but the most salient would be to panhandle under the guise of charity. Each homeless person who signs up gets a table and a jug, urging pedestrians to help those in need by donating whatever they can to the UHO cause. The attendant pays $15 for the table, which comes out of the day’s earnings (along with all the pennies), to UHO; whatever is left in the jug is theirs to do with as they please. Most who donate have no clue that the attendant is homeless. They average about $100 per day.

The organization has garnered criticism that all the money does is buy drugs and booze, but Riley shrugs this off. “If that’s what they want to do with it, they can,” he says “It’s up to them. But some don’t.”

Riley, sitting at a picnic table in Union Square Park and surrounded by members of UHO – gathered today for a meeting and to talk to me – explains that some use it to buy food, or try to stabilize enough to get a job and move up.

Everyone nods, some stare into that thin-air space to consider their own choices. Riley clears his throat, “I did it.”

Riley’s group exists alongside COH, which is government-funded and provides both counseling and other services. “Both need to exist,” Riley says. “Professionals like in the Coalition are people who have intellectually studied homelessness, but have no real first-hand experience. If you put our groups together, you can get something done. We don’t have federal funding, but we think that’s to our credit. We run UHO on wit and spit and we take pride in that. One of the problems with the other programs is that they become institutionalized and lose touch with who these people are. They become numbers and a means to get more funding.” Today, UHO is a bona fide non-profit organization that made $80,000 in 2001.

I’ve been invited to a UHO meeting in Union Square Park early on a Saturday morning. The park is a regular hub for homeless people, young and old. They clump together, going out during the day to panhandle and returning at night to sleep.

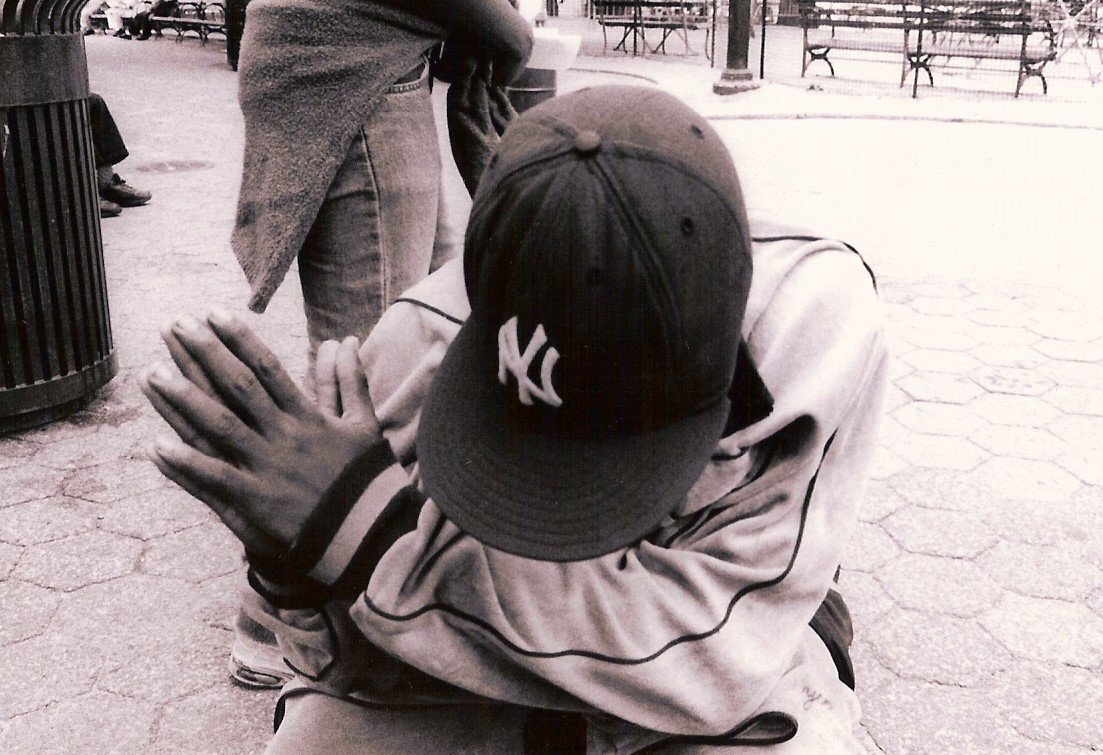

As people gather at picnic tables, one young man in ratty velour warm-ups and a cap saunters around making strange noises. Everyone ignores him. “Please help me,” he calls out in a shrill voice. “Give me money! Why don’t you love me?” Odd bird-like noises erupt from him and he blows through his lips like a baby. Dropping to his knees with his fingers steeples as in prayer, tears flood down his cheeks. My friend hands him three one dollar bills and he rips them to shreds as the tempo of his angst grows. A nameless regular in the park, he’s always strung out. Today they think he’s coming down off PCP. We give him a cigarette, which he gladly accepts and lights. Tears and snot coagulate on his upper lip.

The meeting continues but he grows increasingly distraught. Park security is called. One of the UHO members attempts to placate him by putting an arm over his shoulder. The NYPD arrives on the scene. In moments he is on his belly, cuffed, and loaded onto a gurney – the ambulance taking off with him in back. The meeting continues without emotional responses since this is commonplace.

Many gathered don’t appear homeless. One 30-year-old man, Andrew, claims to have had a top position in a leading NYSE investment firm until it fell under scrutiny for shady trading. This put him on his ass and now he’s on the streets. You wonder about some of the stories but his good teeth, perfect grammar and general carriage make you wonder.

A young Frenchman, Coubadja, reading a dog-eared copy of Sartre, has been in the U.S. for three months. He is homeless as a means for adventure.

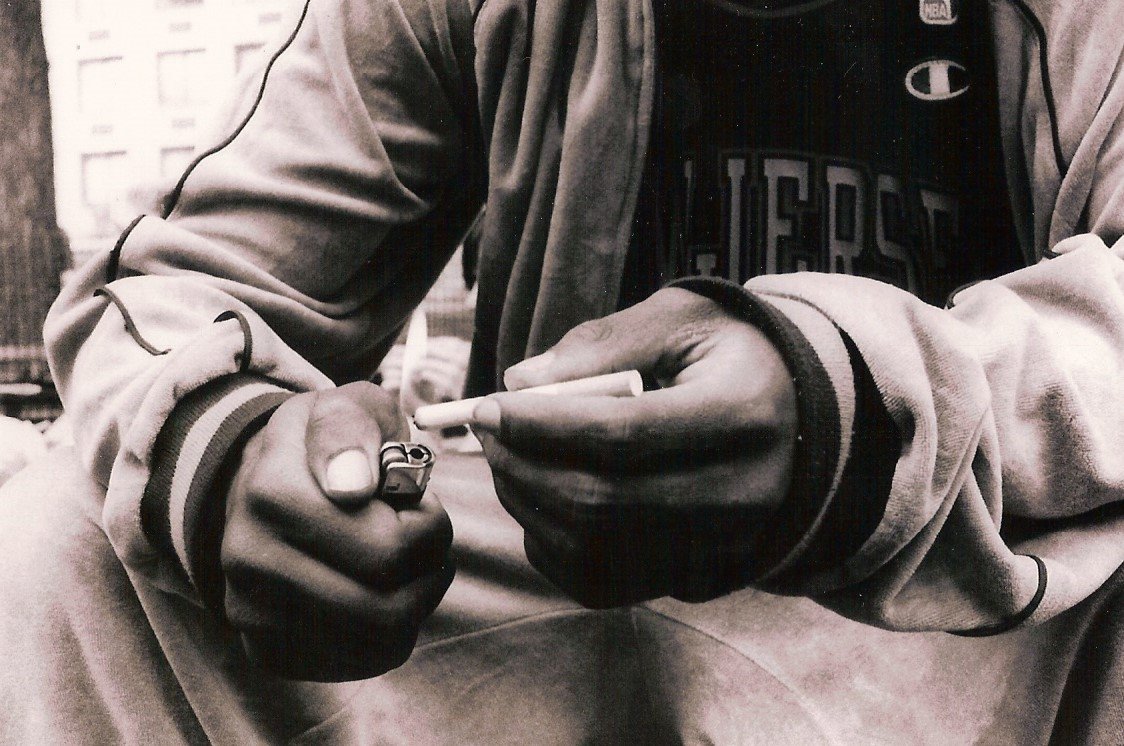

“New York is a big playground. I’ve met some friends here and the weather’s been cooperative,” he says. “You get to see the sights and meet interesting people. People give you things here – I’ve never met people like these before. It is one of the best places to learn about life. Some of these people have a choice to not be out here. Drugs are a common denominator. Everybody has their own poison here. Heroin, pot, pills – a lot of synthetic drugs, too. Stuff being tested in labs,” he says, claiming many here are human guinea pigs for drugs being developed.”

After the meeting I decide to roam in search of more poor nomadic souls. The streets are full of them. Sitting cross-legged on the sidewalk in front of a Popeye’s Chicken, holding an empty cup is a 24-year-old named Phillip Esposito. His mother’s chronic drug problems and bad boyfriends have put them out on the street. She’s still the reason why he keeps going, knowing she needs him. He’s been hustling down in the village, pimping his body out to leering men. “I’ve had guys burn me with cigarettes just for kicks,” he says, adding “Bondage, you name it. If you can imagine it, it’s been done to me. You have to empty yourself out. They drain you. That spark, that little bit of life, it’s gone.”

His hop is that he and his mother and her husband can get off the streets by winter. “I can’t wait to soak my feet in a tub and watch All My Children,” he laughs. “And Buffy. All those important things.” I give him 20 bucks and he nearly cries.

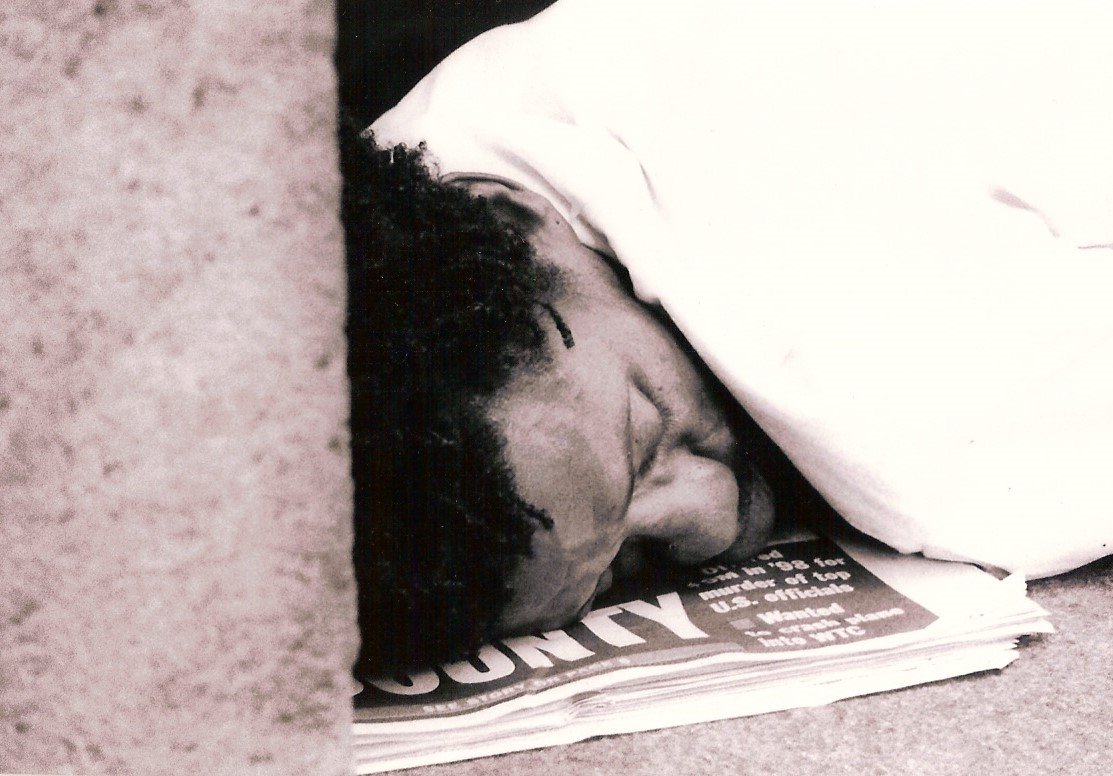

Only a few blocks away I find a Buddha-like character on 5th Avenue reading The Post. There is a K-Mart cart beside him with a cardboard sign leaning against it with hand-written words that read: WE ALL NEED HELP SOMETIMES. We chat and laugh. He’s not crazy, he’s just lost, he says – hasn’t found a good enough map to find his way. He was molested by a family member as a child and ran away from home, spending most of his life on the streets. He hopes he doesn’t ever do the same thing to someone else, it’s something that he worries about. There’s a crack problem – and he’s missing a lot of teeth; but he’s roused to talk easily enough and I’m left feeling like I met a friend, not a freak.

Most people passing easily ignore these cast-offs, as ignorance of the pitiful is a necessary mechanism to protect the heart’s delicate strings, so simply plucked by tragedy and affliction. We, who are well, cower from the reality of our own potential dissolution. They provide the city with a unique form of tithing, giving each person a sense of peace for being selfless and magnanimous if they choose to do so.

“The city coughs up more phlegm of humanity that any other place – where the mind, body and spirit can most cruelly and totally break into pieces. Yet these indigent characters enrich its landscape and add the right spice to the fantastic recipe of Manhattan. In their abject poverty and vulnerable humiliations, they teach us something about ourselves and the regal ugliness of all that is human.”

I stop by a liquor store and buy some Absolut, thinking of Jesus. Heading back to Columbus Circle, I see him from a distance. There he is, glassy-eyed and humming with bravado. Once more, he’s happy to see me, singing songs loud and hitting every note soundly. I give him money which he accepts without looking down – an automatic movement of acceptance; only the increasing volume of his tenor voice singing louder indicates there has been a transaction. Throwing his arms open wide and dramatically, his voice reaches a crescendo and my smile nearly cracks my skull in half.

“Tell me about your life, Jesus,” I say, giving him a peek at the new vodka.

“Ah,” he says, “Sit down, I tell you.”

Once, he says, he was a man.

A singing, dancing man.

His wealthy family in Guatemala was proud of him as a child, so talented in everything it seemed. Great uncle Krafka paid for voice and acting classes for young Jesus. He even had a role in a Chubby Checker movie. But then he fell in love – with America. He would be a big star. Young girls would paste photos of him on the walls of their bedrooms and swoon when they saw him sing.

He discreetly passes me the vodka bottle and I take a big swig. He tells me about Viet Nam, and his wives, and children, and his godmother with the beautiful legs, and we laugh, and he sings, and the sun goes down.